Video text

Before you stands the Nellie Leland building. It was built in 1917 but was converted to luxury lofts in 2003. The neighborhood around you is now known as Lafayette Park, but around the time the Nellie Leland was built, the neighborhood was transforming into vibrant Black Bottom where several successful musicians and athletes such as Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, and Joe Louis grew up. Black Bottom was demolished in the 1960s as part of an urban renewal project that targeted African American neighborhoods and is now recognized for the number of high rises and high rent in the area. But long before this, the neighborhood had German associations.

In 1868, the Arbeiter, or “worker,” Society chose the land in front of you to build a hall for their German American social club. The society supported German American workers by providing aid to sick workers and widows; however, the society fully embraced its social nature. While other German societies sponsored charity festivals and events for children, the Arbeiter Society and hall was infamous for its rowdy parties. The historic Detroit Free Press frequently mentioned these parties because of the noise, fights, and even stabbings. One 1886 article denounced these dances as “disorderly orgies” and “carnivals of crime.”

The hall continued to host dances and society business until 1916. Membership was dwindling and the society felt the neighborhood was changing in a “less desirable” way for such a hall. In 1917, Nellie Leland’s husband Henry, founder of Cadillac and Lincoln, bought the building and demolished it to build an accessible school for disabled children. The school was in operation until 1981. It is remarkable that this building still exists because of its proximity to what was once Black Bottom. It stands as an example of the ever-changing nature of ethnic neighborhoods in Detroit.

Extended text

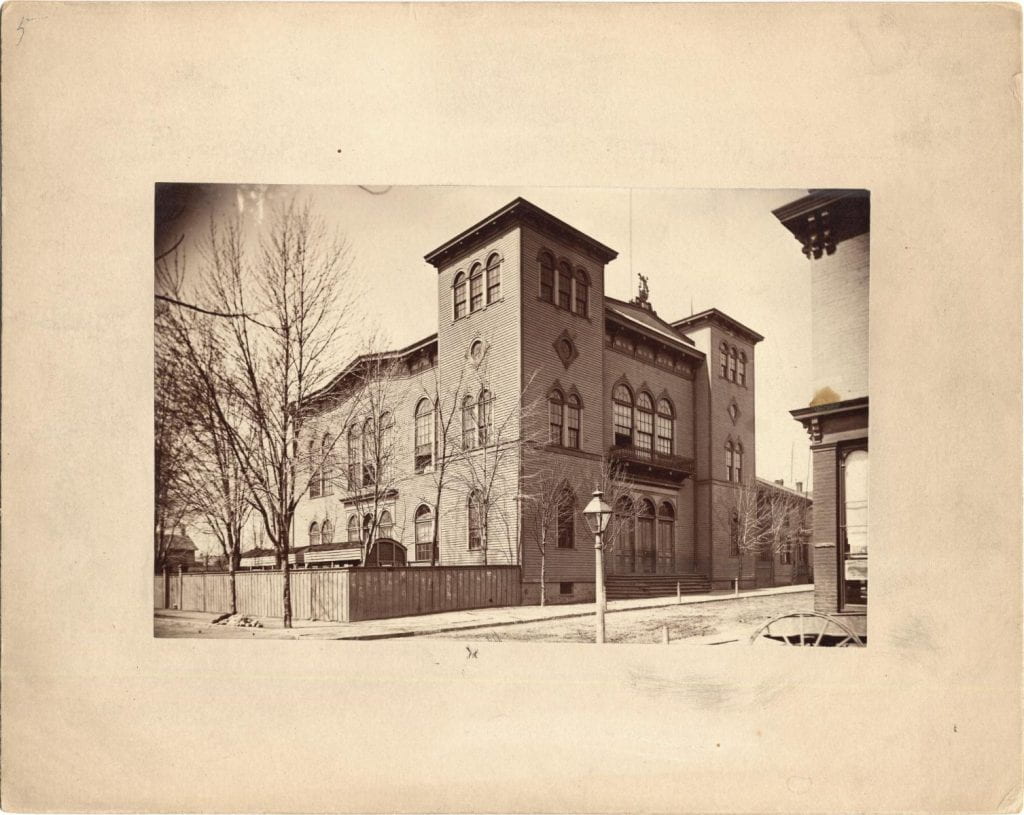

Arbeiter Hall, a gathering place for the Arbeiter Society, was once located on the corner of Catherine and Russell Streets, or what is now Antietam and Russell. The Arbeiter (German for worker) Society was originally formed in the mid-19th century as a social club for German Americans, but it didn’t take long for the society to start supporting injured workers and widows. The society built a hall in 1868 to host meetings and dances, and was rented out for other purposes by non-German Americans until the building was sold in 1916 to Henry Leland. Leland tore down Arbeiter Hall to build an accessible school for disabled children and named the school after his wife Nellie. The Nellie Leland building still stands today as lofts at 1395 Antietam.

Arbeiter Hall was in a similar configuration as the Leland building, but it was made of large and old pieces of lumber. As is the norm for wooden buildings in Detroit, this one burned nearly to the ground in 1885 around 2 a.m. The cause of the fire is unknown, but there was a party and about 300 people had to be evacuated. No party-goers were harmed, but three firemen were injured. The hall was immediately rebuilt, bigger than the first. There was a large beer garden in the rear and several breweries within one block of the hall.

The hall continued to host parties after it was rebuilt, and these gatherings had a reputation for being loud. The Detroit Free Press frequently published articles about rowdy parties at the hall, some more forgiving than others. One article describes the noise as making cheering at a football game sound like a whisper but concludes that “there is no society or combined societies in Detroit or any other burg, that can get so much fun and cheer out of a couple of hours as the Arbeiter boys, even if they are there with the noise.” Another article uses a particular dance at Arbiter Hall where people were injured to argue for the end of all dances in the city of Detroit because the author sees them as “orgies” and “carnivals of crime.”

In addition to social gatherings, the hall also hosted German cultural events that were open to the public. The “Jahr Markt” (annual fair in German) was an annual eight-day event at the hall with entertainment, refreshments, and market stalls selling wares, and the hall was decorated to call Germany to mind. This market was usually economically successful, and all kinds of Detroiters took advantage of the fun.

By the early 1900s, the neighborhood around the hall was changing. African Americans had limited options for places to live in Detroit, but they started to find affordable housing in this area. The Arbeiter Society decided in 1916 to move to a new location and sell their hall, citing an “undesirable” neighborhood change as their reason. Unfortunately, this sort of self-imposed segregation has long been a pattern in Detroit that has continued to today. Nonetheless, a successful and thoughtful group of educators took the opportunity to buy the building at a very low cost to demolish it and build an accessible school for disabled children. This was extremely uncommon for the time, as there were no federal or state mandates for schools to be accessible. Leland made sure the halls were wide and students could easily get to higher stories on a gradual ramp instead of stairs.

The school operated until 1981 and was vacant for years until a developer purchased and converted it to lofts. The building is in the Lafayette Park neighborhood, across from the highrise Pavilion apartments. It is remarkable that the building still stands because the whole neighborhood was razed in the 1950s to build Lafayette Park. This neighborhood was once named Black Bottom by the French for its rich soils, but the name took on another meaning as African American residents and business owners moved in in the early 20th century. Black Bottom was a working-class neighborhood and a lot of the structures were in need of repair by the 1950s, but the neighborhood was also home to important cultural centers like churches and music venues, as well as many successful businesses. Famous talented celebrities like Marvin Gaye, members of the Supremes, and Barry Gordy lived in Black Bottom.

Somehow, the Leland building survived the razing of Black Bottom, and the new lofts are high in demand. The neighborhood no longer has strong ethnic associations, but the rent is high and generally, the apartments in Lafayette Park cater to professionals working downtown. There are no longer any traces of Arbeiter Hall or the surrounding single-family homes and German-American-owned breweries left above the soil.