Discover the tragic story of the son of a Ford employee who helped build GAZ, the first mass-production automobile factory in Soviet Russia

If you were standing at 6094 Ironwood, you would be looking at an empty lot. The house where Victor Herman grew up has long been gone (it burned down not long before he returned from the Soviet Union), and the street he lived on has severely declined over the years. But we can imagine how he and his siblings once played in this neighborhood, and how hard it must have been when their Ukrainian-born father, Samuel Herman, decided to uproot the family and move them to the other side of the world.

It was 1931 and Stalin had signed an agreement with Ford to help him build the Gorky Automobile Factory, the first mass-production automobile factory in the Soviet Union, which was designed by Albert Kahn. Ford sent a group of workers over, including Samuel Herman, Victor Herman’s father. Over 300 Americans went over to work on this project alone, including Walter and Victor Reuther. Tens of thousands of others went to work at other enterprises in the Soviet Union. Some were idealists hoping to build communism, but most were simply in desperate need of jobs during the Depression. Many would never return home, including Victor Herman’s parents, brother Leo, and sister Miriam.

In September 1931 sixteen-year-old Victor stepped from this plot of land and began a tragic journey that would last 45 years. Misfortune struck the family soon after their arrival in Russia: Victor’s mother died of a stroke in 1933. Nonetheless, Victor adapted quickly to his new life, even becoming a celebrity for his record-setting parachute jumping and earning the nickname “Lindbergh of Russia”. But this brief period of happiness soon came to an end. In 1936 Ford terminated the agreement with the USSR which was supposed to last until 1938 but did nothing to notify its employees or get them out of the country. Those left behind had no protection from the Soviet regime, which began harassing, arresting, and imprisoning them, in large part because of Stalin’s paranoia about foreigners.

Victor Herman was arrested for treason in 1938 (for refusing to become a Soviet citizen) and spent the next 10 years in some of the harshest parts of the Stalinist Gulag. After his release in 1948 he was forced to remain in exile in Siberia, and only in 1959 was he able to leave the Russian North and resettle in Kishinev, the capital of Moldova. His father died in 1953 and his brother Leo, who had married Walter Reuther’s ex-girlfriend Lucy, committed suicide in 1974. It took until 1976 for Victor to get permission to leave the Soviet Union. His wife Galina, daughters Svetlana and Janna, and sister Miriam remained behind.

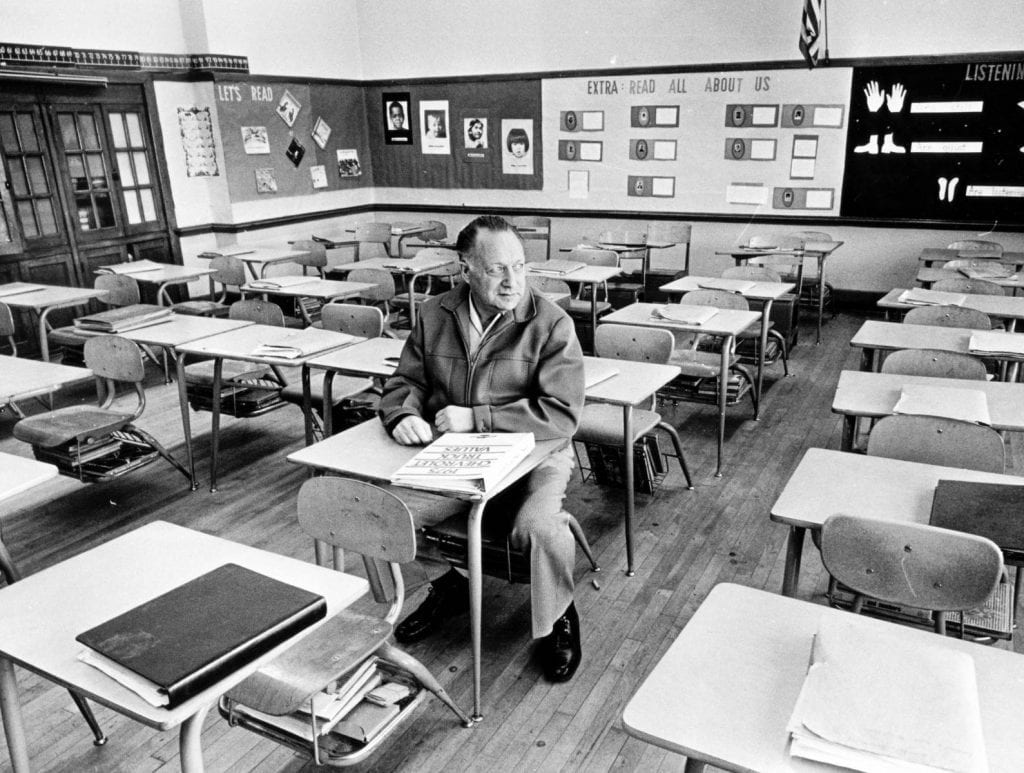

After his return to Michigan in 1976, Herman visited the sites of his childhood and was dismayed at how many no longer existed. Kennedy Square had replaced the old City Hall, Sander’s Bakery on Grand River was closed after the riots in 1967, and, most importantly, his family home had burned down the year before his return. While in the Gulag remembering it had helped him stay alive, but he was too late. He said, however, his house looked just like the white one next store. His school, however, remained intact, and he went inside and walked the halls, filled with memories.

About 6 months after his return he was interviewed by Channel 7 Detroit. At that point Herman was on welfare and living in his sister’s attic; his wife and children were still stuck in the Soviet Union. Canton, MI Attorney Robert Greenstein was touched by Herman’s story and agreed to work pro bono to bring his daughters to the US. He also helped spread the news of Herman’s story to the media to get support for the book Herman was writing about his experience. The results were well beyond anything they could have hoped for. When the daughters arrived in NYC, actor Telly Savalas gave them his suite to use, Frank Sinatra lent them his limo, and the Russian Tea Room closed for an afternoon to serve them. The story made the front page of the New York Times and the family was on Good Morning America. As a result of all the publicity, Herman received a major advance on his book about his experience, $50,000, which represented a significant change in his financial fortunes. When Herman and his daughters returned to Detroit, an unnamed benefactor helped them buy a home and got the daughters into computer school. Soon thereafter Robert Greenstein and Michigan Senator Robert Griffin arranged for Victor’s wife and mother-in-law to come to the US.

Herman spent much of his remaining years fulfilling his promises to his father and other Americans who had shared his ordeal, to tell the truth about the Soviet Union. To this end, he wrote three books, the best-known of which, Coming Out of the Ice, was also made into a TV movie. Another, Realities: Might and Paradox in Soviet Russia, was co-authored by Wayne State University Professor of Geography Fred E. Dohrs. Herman’s books not only chronicle his terrible experience in the prison camps but the lives of a number of other Americans, most from Detroit, brought by Ford to the USSR in the 1930s. Herman also gave talks at a number of Detroit-area churches, labor organizations, and universities, including Wayne State, in Hilberry B in the Student Center in 1977. Just before his death, he was laying the groundwork for a foundation to bring back the remaining Ford employees stranded in Russia. In 1978 Herman sued Ford for abandoning its employees in the USSR. Initially, Ford would not even acknowledge that his father had ever worked for them. The case went through several courts and appeals. Ultimately it was decided in Victor Herman’s favor, although the award was not as much as he had hoped for.

Victor Herman died in 1985 in Southfield, MI. After his death and cremation, the ashes of the former parachute jumper were spread by his family and friends from a plane used by skydivers in Michigan over their jump zone.