Lesley Chapel is a graduate student in History at Wayne State University. Prior to attending Wayne, she earned her Master’s degree in History from Oakland University. Her research interests include the history of Southern identity, the history of emotions, and female identity in early America. Outside of academia, Lesley was an ice dancer for 23 years and served as a US Figure Skating judge for 15 years. It was through her dedication to ice dancing that she discovered her passion for history, as she feverishly researched the life of the legendary Ludmila Pakhomova, the first Olympic Champion in ice dancing.

Lesley plans to use her graduate education in History to pursue a career in academia. She loves sharing her passion for history with others and helping people uncover nuances in historical analysis.

Lavender Magnolias: Heteronormativity, Domesticity, and Lesbian Identity in the South During the 1960s-1970s

Above all, white gay women in the South during the 1960s and 1970s emulated heteronormativity as a way to balance the duality of being a lesbian and being a Southern woman, and perhaps most importantly, they realized that being gay and being Southern were not mutually exclusive identities. - Lesley Chapel

In 1967, lesbian writer Barbara Grier lauded recent literary works that portrayed gay female characters as “perfectly acceptable ordinary members of society.”[1] For white Southern gay women in particular, blending in to heterosexual, “ordinary” society was especially important. Adopting straight norms of white womanhood and domesticity allowed gay women in the South during the 1960s and 1970s to reconcile their Southern identity with their homosexuality. Many white Southerners during this time looked for ways to grapple with the societal changes brought on by the Civil Rights Movement and second-wave feminism. In an attempt to reassert some form of normalcy, many heterosexual white Southern women started clinging to and exalting ideals of feminine domesticity. Interestingly, as white gay women became more self-aware in the South during this era, they also embraced straight norms of Southern domesticity and other heteronormative ideals.

Lesbians in the South displayed an awareness that their predicament was uniquely regional. As Feminary, a lesbian-feminist journal that originated in North Carolina in the late 1970s, attested to, gay Southern women had a distinctive identity that was predicated on being Southern. Feminary proclaimed that,

“As Southerners, as lesbians, and as women, we need to explore with others how our lives fit into a region about which we have great ambivalence…”[2] Feminary continued asserting Southern uniqueness by noting, “We feel we are products of Southern culture and traditions…”[3] The journal established “tell(ing) the stories of women in the South” as one of its main goals.[4]

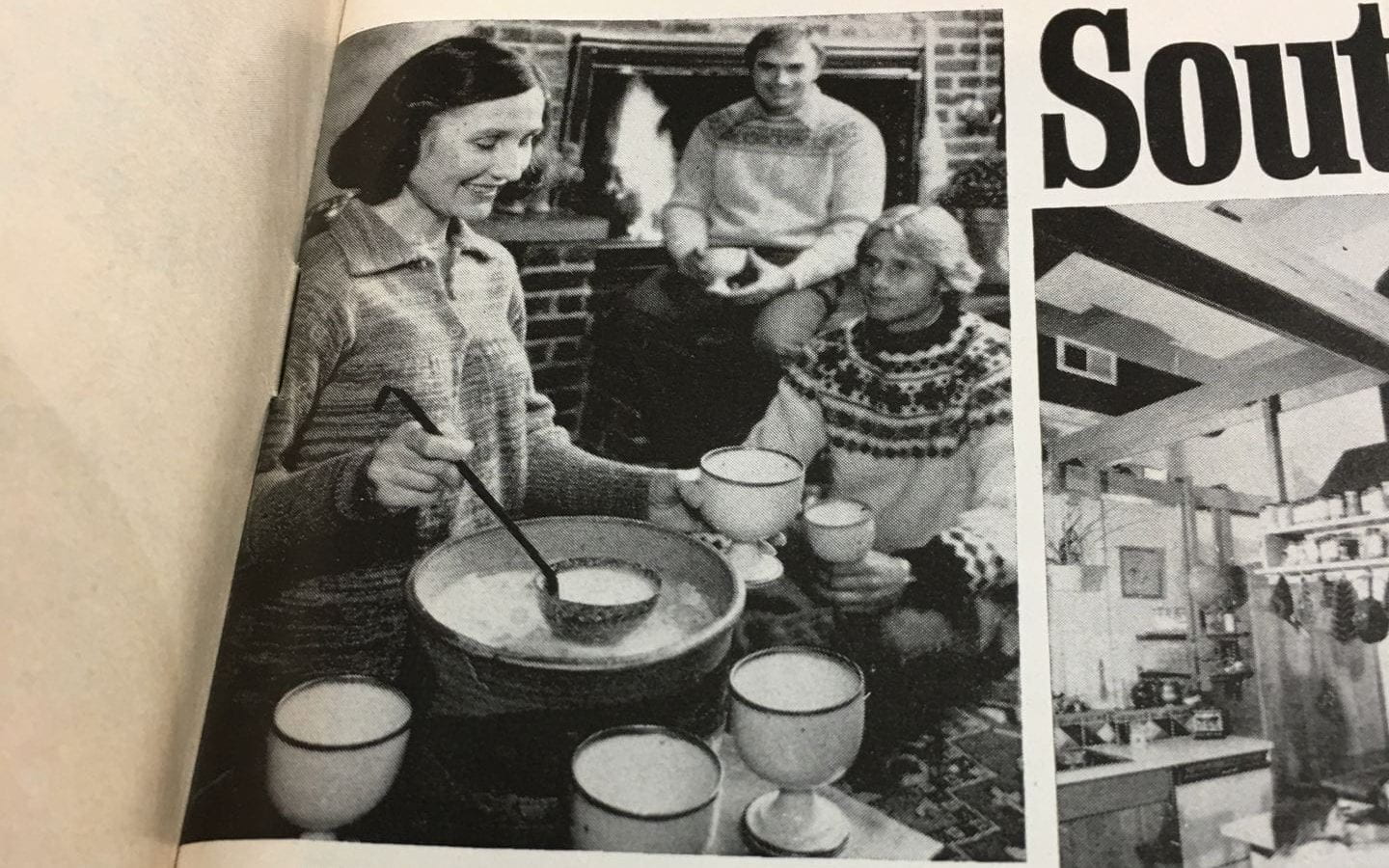

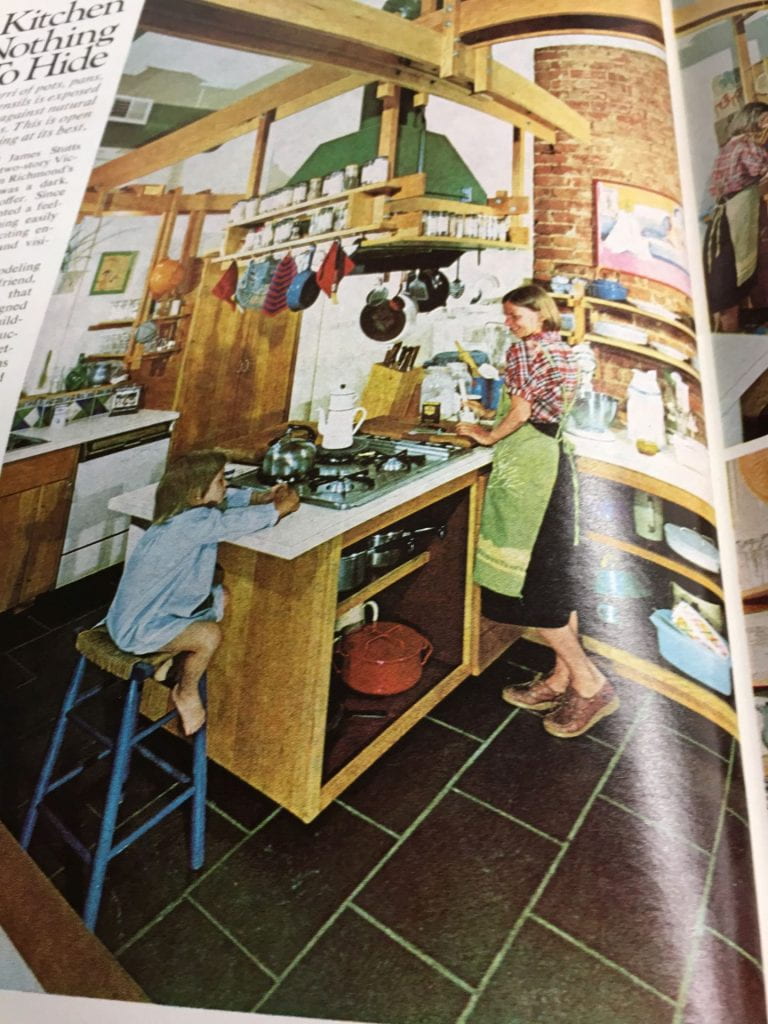

As Southern gay women started coming to terms with their sexuality, they tended to uphold traditional norms of domesticity within their own households. Butch-femme relationships were one way that queer women could carry out concepts of domesticity that echoed heterosexual society. Gay women who identified as femmes often performed traditionally female tasks associated with housework and domestic beautification. For example, Irene, a gay woman from Memphis, recalled that, to her, being a femme meant “(taking) over the housekeeping roles in that particular relationship.”[5] Reflecting on her fifty-year same-sex partnership, Esther, of Tennessee similarly recalled, “The woman I live with does everything your mother would have done in a proper manner.”[6] The performance of heteronormative domesticity for butch-femme couples reflected what was being promoted in Southern popular culture during the 1960s and 1970s. Southern Living magazine, for example, emphasized white women’s place in the Southern household in its articles and in its advertisements. Southern Living, which debuted in 1966 and dubbed itself, “the magazine of the modern South,” promoted domesticity and the ideal white Southern woman as cheerful, well-mannered, and gracious.[7] It is against this backdrop of feminine domestic idealization that the lesbian experience in the South during the 1960s and 1970s can be more fully understood.

The January 1977 and February 1979 issues of Southern Living are useful examples of how the magazine promoted female Southern domesticity. The January 1977 issue ran seven articles on various aspects of home improvement, with women appearing in all six of the photos that corresponded with the articles. Five of the photos featured women exclusively.[8] Likewise, over eighty-seven percent of the home improvement photographs in the February 1979 issue depicted women performing household tasks. Three of the pictures displayed women in the kitchen, while the others showed women cleaning, watering plants, setting dining tables, and doing laundry.[9] As they consumed these types of popular portrayals of idealized Southern domesticity, some gay women, especially those in butch-femme relationships, emulated them. Butch women in butch-femme relationships in the South during this time period also performed in ways that reflected straight Southern ideals of domesticity. Esther, who described her femme partner as doing “everything that your mother would have done,” noted that her role was to do “everything that your father would.”[10] Furthermore, according to Loretta, another Memphis lesbian, the femmes who had butch partners thought of the butches “more as men than as another woman.”[11] Butch performances thus reinforced heteronormative gender ideals in which men were tough, strong, and the antithesis of feminine. These ideals were also reflected in Southern Living. Issues from February and March 1979 featured men performing home repairs like fixing sheet rock and changing a showerhead. Men were also depicted performing lawnmower maintenance and assembling furniture.[12] As popular Southern literature like Southern Living perpetuated strictly defined gender roles, many gay women conformed within their own relationships. Esther, a butch from Memphis, reiterated this phenomenon when she remarked, “My wife runs everything around the house except the lawnmower.”[13]

Esther, a butch from Memphis, reiterated this phenomenon when she remarked, “My wife runs everything around the house except the lawnmower.”[13]

Even Southern gay women who were initially more radical and advocated for homosexual separatism started to emulate straight societal norms throughout the 1970s. This was true of the women involved in the Lesbian Feminist Union (LFU) in Louisville, Kentucky. After the LFU fell apart in 1979, many of its former members abandoned the organization’s previous goal of forming an independent lesbian nation and instead turned their activism towards assimilation into straight society, seeking equal social, economic, and political opportunities for gay women.[14] That their radical goals evolved into assimilation into mainstream white Southern society suggests that Louisville’s lesbians retained an affinity for their Southern identity, and they sought ways to mesh that with their queer identity. As Kathie D. Williams observed, these women were “integrat(ing) their lesbianism into other aspects of their lives.”[15] Thus, Kentucky’s lesbians desired an equal coexistence of their Southerness and their queerness.

Finally, the legal landscape of the South presented greater incentive for queer people to blend in with straight society. Specifically, anti-sodomy laws criminalized gay sex, and while such laws were primarily directed at gay men, knowing that the legal system viewed gay sexual activity as unlawful undoubtedly caused many Southern lesbians to hide or otherwise obscure themselves. Furthermore, anti-sodomy laws have persisted in many Southern states well into the twenty-first century, even after the Supreme Court deemed them unconstitutional in its 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision.[16] In Louisiana in 2014, for example, the state legislature voted to keep anti-sodomy laws in place. This came as a relief to some of Louisiana’s straight residents, and as one conservative activist put it, gay sex is simply “not a Louisiana value.”[17] This kind of mentality demonstrates the high degree of historical and persistent homophobia prevalent in Southern states, and it accounts for one reason why the region’s queer population has kept itself hidden from or otherwise amalgamated into heteronormative society.

While the South’s conservative straight residents have maintained that homosexuality is incompatible with Southern values, the region’s gay women have sought ways to reconcile the queer and the Southern components of their identities. As Elizabeth McCain, a self-described “lesbian belle,” noted, “I’m still obviously very Southern. I’ve never lost that identity, and that’s always been really important to me.”[18] For McCain and white Southern lesbians during the 1960s and 1970s, being gay and being Southern often meant emulating heteronormative domestic mores as promoted in magazines like Southern Living. It meant aligning with conventional gender norms and performance in butch-femme relationships. Above all, white gay women in the South during the 1960s and 1970s emulated heteronormativity as a way to balance the duality of being a lesbian and being a Southern woman, and perhaps most importantly, they realized that being gay and being Southern were not mutually exclusive identities.

[1]Quoted in Jaime Harker, The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 22

[2]Feminary: A Feminist Journal For the South Vol. 9, Issue no. 1 (Spring 1978).

[3]Feminary: A Feminist Journal For the South Vol. 9, Issue no. 1 (Spring 1978).

[4]Ibid.

[5]Irene (pseud). Interview by Daneel Buring. Tape recording and transcript in possession of interviewer. Memphis, Tennessee, 16 September 1994. Quoted in Buring, “Softball and Alcohol: The Limits of Lesbian Community in Memphis from the 1940s through the 1960s,” in Carryin’ On in the Lesbian and Gay South, ed. John Howard (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 208.

[6]Esther (pseud.) Interview by Daneel Buring. Tape recording and transcript in possession of interviewer. Memphis, Tennessee, 19 August 1994. Quoted in Buring, 209.

[7]Southern Living, February 1979, 5.

[8]“Liven Up Traditional Cabinets,” “Stove Sits On a Quarry Tile Base,” “It’s Easy to Make a Fabric Frame,” “Warming Up a Master Bedroom,” “Framing Enhances a Mirror’s Image,” “A Cornice Plus Crown Molding,” “Townhouse Centers on an Atrium Surprise,” Southern Living, January 1977, 104-118.

[9]“A Kitchen With Nothing To Hide,” “Wall Has a Surprise Opening,” “Unexpected Places For Stained Glass,” “New Space For Family Living,” “Crafted With Houseplants in Mind,” Southern Living, February 1979, 130-132, 134, 137, 142.

[10]Buring interview with Esther. Quoted in Buring, 209.

[11]Loretta (pseud.) Interview by Daneel Buring. Tape recording and transcript in possession of interviewer. Memphis, Tennessee, 10 July 1995. Quoted in Buring, 208.

[12]“Around the House,” Southern Living, February 1979, 144, and “This Table Is Rough and Ready,” “Spring Mower Maintenance,” Southern Living, March 1979, 124-125, 154.

[13]Esther interview by Buring. Quoted in Buring, 209.

[14]Kathie D. Williams, “Louisville’s Lesbian Feminist Union: A Study in Community Building,” in Carryin’ On in the Lesbian and Gay South, ed. John Howard (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 234.

[15]Williams “Louisville’s Lesbian Feminist Union,” in Howard, 234.

[16]“12 States Still Ban Sodomy a Decade After Court Ruling,” USA Today, April 21, 2014, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/04/21/12-states-ban-sodomy-a-decade-after-court-ruling/7981025/. Accessed December 16, 2021

[17]Ibid.

[18]Sherry Lucas, “A Lesbian Belle’s Out and Proud Path From Mississippi to the Stage and Page,” Mississippi Free Press, June 9, 2020, https://www.mississippifreepress.org/3695/a-lesbian-belles-out-and-proud-path-from-mississippi-to-the-stage-and-page/. Accessed December 12, 2021.

Check out our other Student Projects!

Translating historical research for public audiences