Lindsay Ragle-Miller

Do the names we call each other really matter? Terms of endearment, like “dear,” “sweetheart,” and “love,” appear in many of the Women Warrior (WW) ballads, but what is interesting is who uses them, when, and why. While reading the ballads, I was curious about the terms of endearment (TOE) used by WW and their lovers. Scholarship on this subject is limited and has mostly focused on the qualitative aspects of the relationships. Very little has been done on quantitative elements of these relationships. Although TOE can be used in any relationship, this paper focuses on the ones shared between lovers. According to the OED, an endearment is “an action or utterance expressive of love or fondness; a caress.” My research began with the following questions:

- What do the terms of endearment (TOE) the WW and her Cis-Male Lover (CML) use imply about their relationship and feelings toward one another?

- How and why do the TOE change when the WW is cross-dressed?

- Do they change again when the WW reverts to female dress?

The research available on this subject is surprisingly limited, but it does support the idea that the TOE that people use in their relationships matter, and that those TOE change over the course of the relationship. This paper tracks the terms that the women warriors and their lovers use when addressing each other and analyzes what their usage and placement mean in the larger contexts of the women warrior ballads. I will examine the contemporary scholarship on TOE and the historical contexts of the research, then introduce the methods of my data collection and share my results.

Literature Review

Several theories exist as to why we use pet names and TOE as adults. Most commonly, lovers use TOE with each other “to establish or maintain a social relationship between the speaker and the addressee(s).”[i] Studies have shown that creation and usage of TOE is at the highest level during the preliminary stages of the relationship. “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” by Hopper, Knapp, and Scott provides a general summary of the idioms that people use with their significant others. As Hopper et al show, “Personal idioms are most characteristic of the early phases of a … relationship.”[ii] In longer established relationships, TOE usage often serves to remind lovers of happy memories or to encourage playfulness.[iii] Leslie Baxter argues, “Because symbols emerge out of a time-specific context in the relationship’s history, they may serve to link the past to the present and thereby to bridge a transition between the familiar past and forces of novelty and change.”[iv] In other words, couples create TOE early in the relationship to create and reinforce their nascent bond, while their later use of TOE reminds the lovers of their history as well as buttresses their continuing relationship.

Some theorists believe that “the reason people in relationships use pet names for their partners is because they’re harking back to their own childhood experience and to their first love, their mother.”[v] Mothers often use baby talk, which can include TOE, to their babies, and one theory argues that we are seeking to correlate our relationship with our partner with our first meaningful relationship with our mothers. Similarly, “another reason we call each other “babe,” “sweetheart” and “sugarpuff” (or your term of endearment of choice) is that doing so taps into our innate desire to play”, again harkening back to our childhood.[vi] TOE allow partners to be playful while building a stronger bond with each other.

Finally, there is some evidence that creation and use of TOE relates to power dynamics within the relationship. Thomas Honegger argues that assigning a nickname to a partner shows “his desire to re-create the beloved’s personality and to possess her entirely, likely to try and create a private counter-world and to cut as many of the bonds as possible that bind his beloved to society and the public sphere.”[vii] This is a more pessimistic view on TOE but has some merit when applied to Early Modern WW ballads. In all relationships, nicknames of all types “may illuminate norms associated with power, expertise, or affection,” all three of which can be expressed through TOE.[viii] TOE are the most intimate form of nickname, as they can cause embarrassment if revealed in public, giving the user power over the other’s emotional state as well as a means of expressing affection. When you can call someone “snooky ukums” in public, you have the power to cause them great embarrassment.[ix] Therefore, TOE can express both affection and power. These findings in contemporary scholarship on TOE support the assumption that TOE in the ballads not only give information on how lovers communicate, but also how their choices of words express love and power.

Gender also influences the power dynamics of TOE. In a [give date] study, “both males and females credited the males with originating the majority (99) of idioms… This may mean that the husbands make more idiom suggestions, or it may mean that male-suggested idioms are more likely to “stick.”[x] If males create and use idioms more, then they also have the power that can come along with using those idioms. This power imbalance is indicated by what Boasso et all call “benevolent sexism” in relationships. Although there are three elements of benevolent sexism, ”protective paternalism, complementary gender differentiation, and heterosexual intimacy”, in the WW ballads, heterosexual intimacy is the most prevalent. According to Boasso et al, “Heterosexual intimacy is the belief that a man is not complete unless he has a woman romantic partner. Under these belief systems, women are consigned to traditional gender roles and romanticized as sexual objects in the eyes of men, effectively constraining women to live within certain limits of behavior.”[xi] By using these idioms in a public sphere, both partners have power over their lover; however, according to this research, because men create and use more idioms they have a disproportionate amount of power, playing into the benevolent sexism of heterosexual intimacy.

The specificity of idiom use between partners also gives insight into the relationship. Studies have shown more specific and unique idioms give a perception of increased closeness in the relationship. “Perceived uniqueness was associated with both perceived closeness of the relationship and the stage of the relationship. Extending this concept to actual communicative behavior suggests that there will be a more idiosyncratic system for more intimate relationships.”[xii] As the relationship becomes more intimate, communication, including nicknames, between the couple become more individualized. Even when the personal idioms are negative or critical, i.e. ”fumblefingers,” ”the act of developing and using personal idioms is perceived by couples to have a positive effect on their relationship.”[xiii] Personalized TOE reflect an increased closeness in a relationship, which I hypothesized will be evident in the ballads. By examining the usage of TOE in the ballads, we will gain knowledge about the relationships between the lovers.

Currently, we take it for granted that most people will marry for love; however, this was a revolutionary idea that was still gaining popularity, especially in the upper classes, during the Early Modern period. Before the increase in companionate marriage, “marriage was not an intimate association based on personal choice.”[xiv] For the upper and middle classes, marriage was an alliance for political and economic gain, while the lower classes married for labor and economic advantages. Affection might grow within the relationship, but it was not the reason for marriage. After 1640, political and theological changes brought about the rise of ”Affective Individualism,” or companionate marriage, where the family was “organized around the principle of personal autonomy, and bound together by strong affective ties.”[xv] Affective Individualism, like most cultural changes, progressed at different rates in different social classes. Because the upper and middle classes held more property and wealth, companionate marriage was much slower to catch on than in the lower classes.

Before companionate marriage, marital satisfaction was not based on emotional attachment, so idioms were likely not very necessary or specific. After affective individualism, emotional satisfaction became increasingly important, so use of TOE became commensurately critical. Instead of addressing their partner as ”sir” or ”madam, ”husband” or ”wife”, TOE became common. For example, Richard Steele’s (a middle class man during the 1800’s) letters, found in The Family, Sex and Marriage by Joseph Stone, show how TOE can evolve over the course of a marriage. “[I]mmediately after his marriage, Richard Steele addressed his wife as ‘Madam,’ but soon slid into ‘Dear creature,’ ‘My loved creature,’ ‘My dear.’ Within a few months, however, he was writing to her as ‘Dear Prue’,” a more personalized TOE.[xvi] However, it was already more common for men to use TOE, as the patriarchal nature of marriage encouraged women to address their husbands formally. Women were still encouraged to address their husbands as ”sir” or ”husband.” Based on the history of companionate marriage, I was interested to see if the changes in cultural perceptions of relationships was evident in the usage of TOE in the WW ballads. In order to track and analyze the usage of TOE, I gathered data from the 113 ballads in the Diane Dugaw catalogue. I will discuss my methodology for gathering and interpreting data in the next section.

Methodology

Taking a cue from our previous data-gathering, I created a spreadsheet. In this spreadsheet, I listed all the ballads, including Dugaw catalogue number and noted if they include love language. Then, I divided the spreedsheet into four catagories: WW dressed as a female (Female), the WW’s cis-male lover (Male Lover), the WW while cross-dressed (FTM Warrior), and the WW after she returned to female dress (Ret to Fem). Finally, for the Female and Male Lover categories, I added columns for the six most common TOE: love, dear/my dear, dearest, true love, jewel, sweet/sweetheart. In addition, I added a category for miscellaneous TOE. For the FTM and Ret to Fem categories, I did not include the most common TOE, but simply wrote them out in the columns. After I created the spreadsheet, I re-read all the ballads and marked who used which TOE. I only counted terms that were used in direct speech by the WW or the Male Lover; I did not track words used by a narrator or in the third person. I chose this method of tracking the TOE so that I could analyze the words in relation to how the characters feel about each other. By not including the TOE used by the narrator, I intended to focus on what the words meant to the characters who used them. When the CML used a TOE to the WW while cross-dressed, I made a note in the column next to the notation for the term they used. Finally, I highlighted the ballads in which the WW used TOE while cross-dressed.

After the spreadsheet was finished, I tabulated the results into a separate spreadsheet, counting the number of times which TOE were used. It should be noted that the final numbers are representing the number of times the TOE were used in the ballads, not the number of ballads in which TOE were used. Finally, I created several graphs with the information, highlighting areas that I thought were interesting. This area of research, as well as the methods involved in this kind of analytical study, are familiar to me but not the type of work I would normally undertake, and I was excited to try a new method of writing and research.

Results

After evaluating the results, I found 311 uses of TOE total across the ballads.

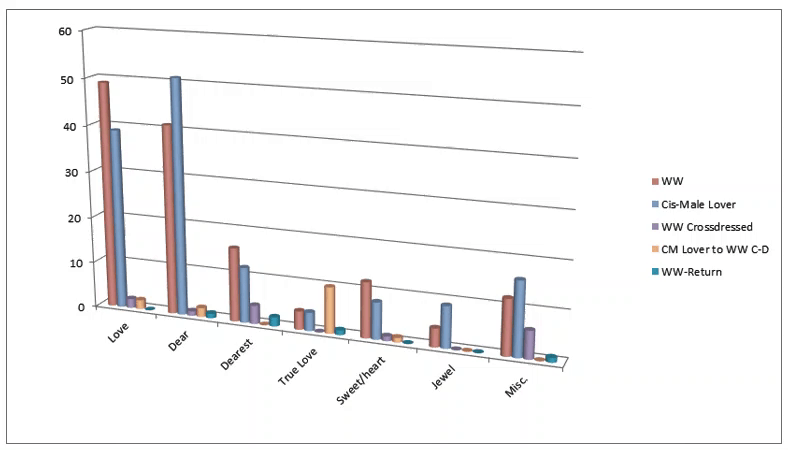

| WW | Cis-Male Lover | WW Cross-dressed | CM Lover to WW C-D | WW-Return | |

| Love | 49 | 39 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Dear | 41 | 51 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Dearest | 16 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| True Love | 4 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| Sweet/heart | 12 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Jewel | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Misc. | 12 | 16 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 138 | 139 | 14 | 15 | 5 |

The WW and the CML used TOE about the same amount, although the terms that they used the most frequently were different. The WW (Female) used the term “love” most frequently, while her CML (Cis-Male Lover) used “dear” most often. The Cis-Male Lover also showed more freedom in their TOE, as they used miscellaneous TOE more often than any other category. Interesting, the WW cross-dressed used miscellaneous TOE more than they did any other TOE. Also, the CM Lover to the WW while cross-dressed used the term “true love” more than any other, while the CML used “jewel” more than any other category.

TOE in WW Ballads

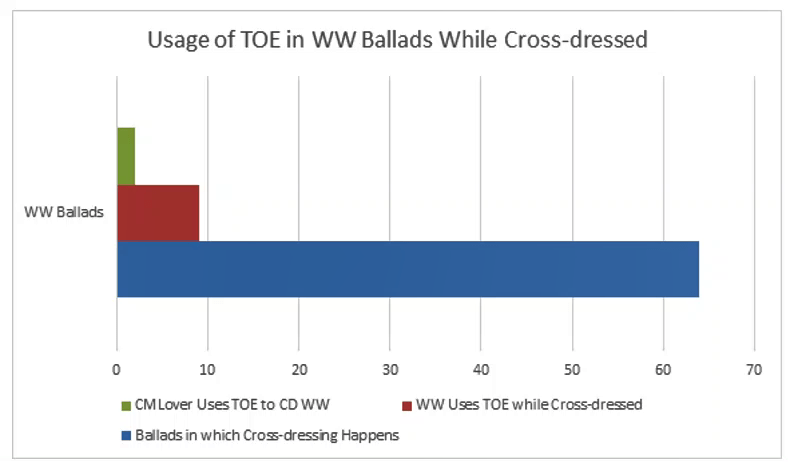

Of the 63 WW ballads in which cross-dressing happens, the WW uses TOE while cross-dressed in 9, and the CML (lover) uses TOE to the WW while they are cross-dressed in 3 ballads.

Conclusions

In order to effectively answer the research questions that were posed at the beginning of the paper, I will address them one at a time.

- What do the terms of endearment (TOE) the WW and her Cis-Male Lover (CML) use imply about their relationship and feelings toward one another?

Although the WW and the CML use TOE with about the same frequency, CML use significantly more miscellaneous terms, supporting the research that argues men create more idioms. Interestingly, this aspect of communication was mimicked unconsciously by the writers of these ballads. The WW generally uses more generic terms, while the CML’s usage of more unique personal idioms reflects the gendered difference and power imbalance in relationships, specifically in the Early Modern period. Importantly, though, this trend in gendered TOE use changes when the WW is cross-dressed.

- How and why do the TOE change when the WW is cross-dressed?

When the WW is cross-dressed, they use more miscellaneous TOE than they do at any other time. This could be reflective of their new role as a perceived male. As a male, they would likely adopt the similar TOE as the CML, so they would use more miscellaneous terms, like the CML. The authors of these ballads, low brow though they were, instinctually varied the speech patterns to show the impact that crossdressing has on the characters in the ballad; this was clearly an integral part of speech at that time. Another reason that the WW uses more miscellaneous TOE could be related to the queerness of the relationship while the WW cross-dresses. As Peggy Chin has argued about TOE in contemporary queer relationships, “LGBTQ people have struggled with terminologies to declare to each other and to others the nature of their important relationships.”.[i] The WW, while cross-dressed, needs new terms to address their lover ( or adopt the kinds of TOE that men use), so s/he creates his/her own. Further, as I discuss below, once the WW returns to female dress, the usage of TOE changes again.

- Do they change again when the WW reverts to female dress?

Although there are very few ballads in which the WW reverts to female dress and addresses her lover with TOE, when she does, she uses “dearest.” Before she cross-dresses, the WW uses “dear” frequently, although not as much as “love,” so why does she change to the superlative “dearest” after she cross-dresses and returns to feminine dress? According to research, making sacrifices for a partner, such as enduring hardship while enlisted the military dressed as a man, “may lead to increased pleasure and positive emotions through the process of empathic identification.”[ii] After she returns to feminine dress, the WW is likely more invested and positive about the relationship, resulting in the use of the superlative form of ”dear,” ”dearest.” This psychology also helps to explain why the highest proportion of TOE used by the CML to the WW while cross-dressed “true love.” ”Perceiving that one’s partner has sacrificed for approach motives was associated with greater positive affect, satisfaction with life, and satisfaction in the relationship.”[iii] After realizing how much his partner is ready to sacrifice for their relationship, the CML is more likely to call the WW ”true love,” as he has greater satisfaction in the relationship.

A final question that arose during the research stage was: Why was the proportion of TOE by WW while cross-dressed so low? The low proportion of TOE by WW while cross-dressed likely results from both the desire to remain in disguise and the lack of direct address attributed to the WW while cross-dressed. This lack of direct address is possibly a form of queer erasure, the practice of removing queer experiences and characters from history and culture. The aggressive heteronormativity of the Early Modern period might have restricted the attribution of direct speech by the WW while cross-dressed in order to maintain the status quo.[iv]

Conclusions:

Although I feel that I have answered the research questions I had at the start of the paper, there is so much more analysis that can be done with this data. Dugaw’s catalogue offers a rare case study of interrelated ballads which permit this kind of detailed quantitative analysis in new and unique ways. Future areas of research on TOE in this genre might include: examining the chronology of the ballads in relation to the terms and usage of TOE; detailed examination of the nine ballads in which the WW uses TOE while cross-dressed; more research into the origins and usage of the terms “love” and “dear,” to determine why they were the most popular terms used; and many more. Hopefully, the research and data collection I have done here will give support and guidance for people examining these ballads in the future.

Bibliography

Baxter, Leslie A. “Symbols of Relationship Identity in Relationship Cultures.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4, no. 3 (Aug. 1987): pp. 261–280, doi:10.1177/026540758700400302.

Boasso, Alyssa, Sarah Covert, and Janet B. Ruscher. “Benevolent Sexist Beliefs Predict Perceptions of Speakers and Recipients of a Term of Endearment.” Journal of Social Psychology 152, no. 5 (September 2012): 533–46. doi:10.1080/00224545.2011.650236.

Bruess, Carol J. S., and Judy C. Pearson. “Sweet Pea’ and `Pussy Cat’: An Examination of Idiom use and Marital Satisfaction Over the Life Cycle.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,10, no. 4 (1993): pp. 609-615.

Chin, Peggy. ”Terms of Endearment: Not Just Semantics,” Lavender Health, 7 February 2016, https://lavenderhealth.org/2016/02/07/terms-of-endearment-not-just-semantics/.

Clyne, Michael G., et al. Language and Human Relations : Styles of Address in Contemporary Language. Cambridge University Press, 2009. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=273807&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Honeger, Thomas. “Nominal Forms of Address in Middle English: Pet Names and Terms of Endearment Between Lovers.” In Anglistentag2003 MŸnchen, edited by Christoph Bode, Sebastian Domsch and Hans Sauer, 39-55. Trier, 2004. https://www.academia.edu/12276116/_Nominal_Forms_of_Address_in_Middle_English_Pet_Names_and_Terms_of_Endearment_between_Lovers._

Hosie, Rachel. “The Scientific Reason Why People Use Pet Names for Their Partners.” Independent.10 Dec. 2017, www.independent.co.uk/life-style/love-sex/reason-why-people-couples-use-pet-names-partner-baby-talk-sweetie-parents-bonding-mother-love-a8101856.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

Hopper, Robert, Mark L. Knapp, and Lorel Scott. “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk.” Journal of Communication, vol. 31, no. 1 (1981): 23-33.

Knapp, Mark L., et al. “Perceptions of Communication Behavior Associated with Relationship Terms.” Communication Monographs, vol. 47, no. 4 (Nov. 1980): 262. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/03637758009376036.

Impett, Emily A., Shelly L. Gable, and Letitia Anne Peplau. “Giving up and Giving in: The Costs and Benefits of Daily Sacrifice in Intimate Relationships.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89, no. 3 (September 2005): 327–44. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.327.

Stone, Joseph L. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800. New York: Harper & Row, 1977. Yep, Gust. Queer Theory and Communication : From Disciplining Queers to Queering the Discipline(s). Florence: Routledge, 2004. Accessed December 9, 2

Endnotes

[i] Clyne et al, Language and Human Relations : Styles of Address in Contemporary Language (Cambridge University Press, 2009), EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=273807&site=ehost-live&scope=site, 100.

[ii] Robert Hopper, Mark L. Knapp, and Lorel Scott “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” Journal of Communication, vol. 31, no. 1 (1981): 24.

[iii] Hopper, Knapp, and Scott, “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” 24.

[iv] Leslie A. Baxter, “Symbols of Relationship Identity in Relationship Cultures,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 4, no. 3, (Aug. 1987),263, doi:10.1177/026540758700400302.

[v] Rachel Hosie, “The Scientific Reason Why People Use Pet Names for Their Partners,” Independent, (10 Dec. 2017): www.independent.co.uk/life-style/love-sex/reason-why-people-couples-use-pet-names-partner-baby-talk-sweetie-parents-bonding-mother-love-a8101856.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

[vi] Hosie, “The Scientific Reason.”

[vii] Thomas Honeger, “Nominal Forms of Address in Middle English: Pet Names and Terms of Endearment Between Lovers,” Anglistentag2003 MŸnchen, edited by Christoph Bode, Sebastian Domsch and Hans Sauer, (Trier, 2004): 44. https://www.academia.edu/12276116/_Nominal_Forms_of_Address_in_Middle_English

[viii] Hopper, Knapp, and Scott, “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” 24.

[ix] Hopper, Knapp, and Scott, “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” 24.

[x] Hopper, Knapp, and Scott, “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” 29.

[xi] Alyssa Boasso, Sarah Covert, and Janet B. Ruscher, “Benevolent Sexist Beliefs Predict Perceptions of Speakers and Recipients of a Term of Endearment,” Journal of Social Psychology 152, no. 5 (September 2012): 534, doi:10.1080/00224545.2011.650236.

[xii] Mark L.Knapp, et al., “Perceptions of Communication Behavior Associated with Relationship Terms,” Communication Monographs, vol. 47, no. 4, (Nov. 1980), p. 265, EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/03637758009376036.

[xiii] Hopper, Knapp, and Scott, “Couples’ Personal Idioms: Exploring Intimate Talk,” 31.

[xiv] Joseph L. Stone, The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800 (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 745).

[xv] Stone, The Family, Sex and Marriage, 795.

[xvi] Stone, The Family, Sex and Marriage, 6941.

[xvii] Peggy Chin, ”Terms of Endearment: Not Just Semantics,” Lavender Health, (7 February 2016), https://lavenderhealth.org/2016/02/07/terms-of-endearment-not-just-semantics/.

[xviii] Emily A .Impett, Shelly L. Gable, and Letitia Anne Peplau, “Giving up and Giving in: The Costs and Benefits of Daily Sacrifice in Intimate Relationships ” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89, no. 3 (September 2005): 329. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.32

[xix] Impett et al., ”Giving Up and Giving In,” 340.

[xx] Gust Yep, ”Queer Theory and Communication : From Disciplining Queers to Queering the Discipline(s),“ (Florence: Routledge, 2004), Accessed December 9, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central.