Matthew Jewell

In an effort to better understand the cultural contexts and generic structure of the Warrior Women ballads found within Dianne Dugaw’s catalogue, this essay will examine early modern street literature which prominently features the character of the “Warrior Man.” For the purposes of this project, I will use the term “Warrior Men” to describe soldiers who are gendered male as well as combatants who are not explicitly gendered but still fall under an early modern understanding of the term “soldier.” Furthermore, I have narrowed my analytical scope to the seventeenth century, a time of complex and prolonged political conflict when broadside ballads enjoyed immense popularity. This constraint allows for a detailed study of specific elements of early modern street literature, but it admittedly cannot account for every theme or doctrine found in ballads which feature male soldiers. Still, an exploration of the broad thematic “norms” of street literature regarding war reveals how the Warrior Women ballads diverge in content from works of the same genre.

With this generalized framework in place, intriguing thematic commonalities emerge across the Warrior Men ballads. While several focus intently on the strife and deadliness of the battlefield, others take the form of dialogues between lovers separated by impressment, a trope which intersects with the themes present in the Warrior Women ballads. Still another popular trend involves ballads which praise English soldiers for their military prowess and valorize key military figures such as William of Orange and the earl of Essex. However, this essay will focus on the Warrior Men ballads’ recurring and robust expressions of religiosity, a trend which unveils prevalent cultural and historical themes, which may complicate our understanding of the ballad genre. In response to the reportedly ambivalent and sometimes fearful dispositions of soldiers, many of whom were “pressed to war” against their will, the Warrior Men ballads assume the unique task of offering spiritual encouragement, often appealing to the Christian faith of men to serve willingly for the glory of God and their country. As such, the Warrior Men ballads provide a variety of Biblical quotes and allusions, celebrate commanders and political figureheads who embody “ideal” practices of Christianity, and exude profound anti-Catholicism in favor of Protestantism and the continued reformation of the Church of England. Collectively, the ballads argue that a religiously-enlightened England has incurred God’s favor, an attempt to convince their audience, which may well have included young, lower-class, war-bound men and their families, that England’s success on the battlefield is all but assured under the eyes of a sympathetic God who is “on Protestant England’s side.”

In focusing on the prevalence of Christian themes in the Warrior Men ballads, this essay is at odds with conversations about religion and ballads in the seventeenth century. In fact, several scholars have documented a distinct shift away from religious messages in street literature toward the end of the early modern period. For instance, in “The Ballad’s Seaman: A Constant Parting,” Patricia Fumerton notes that early modern sea ballads in particular “are mostly secular, with only nods to the ‘heavens’ or ‘God’ in the context of a maid praying for her seamen’s safety, seamen facing possible shipwreck at sea, or celebrations of a victory against an enemy” (135). This commentary joins the discourse established by Natascha Würzbach’s The Rise of the English Street Ballad, 1550-1650. There, Würzbach argues, “Over the period from 1550 to 1650 there is an obvious change in the content of the English street ballad, from religious materials and themes in the second half of the sixteenth century to the treatment of secular themes in the first half of the seventeenth century” (236). Reaching back even further, Louise Pound claims that while “the oldest ballad texts have to do rather strikingly with the church… [the ballad] passes from ecclesiastical hands, with edification the purpose, into secular hands, with the underlying purpose of entertainment” (163-6). While the trend highlighted by Fumerton, Würzbach, and Pound holds true for the 133 Warrior Women ballads of Dugaw’s catalogue, which feature only scant references to religion and God, it cannot account for the 17th-Century Warrior Man ballad’s preoccupation with historical events and conflicts in which religion and the English reformation play central roles.

One explanation for the divergence of these themes can be analyzed from the standpoint of generic conventions. The Warrior Woman ballad’s emphasis on love, courtship, marriage, and domestic life indicate that it is essentially a romance crafted for the purposes of entertainment. Meanwhile, the Warrior Men ballads I will analyze in this essay display propagandic inclinations which suggest that they would have been sung and distributed for distinct Protestant sociopolitical purposes (though there are certainly Warrior Women ballads such as “The Protestant Commander” which have their own religious agendas). For example, a number of Warrior Men ballads engage in the tense religious discourse surrounding the English Civil War. These ballads often favor the political aims and religious reforms advocated by the parliamentarian faction, which sought to limit the power of Charles I while “purifying” aspects of the Church of England that strayed too close to Catholicism, namely, elements of the liturgy and the hierarchal structure of the episcopacy. Relatedly, other Warrior Men ballads confidently support William of Orange, a Protestant king whose Glorious Revolution of 1688 and subsequent campaigns in Ireland overthrew and defeated James II, a Catholic monarch. With these similitudes in mind, I argue that the dissemination of religious and political propaganda through the Warrior Men ballads ultimately serves as a method of incentivizing men to willingly enlist themselves, the stakes being the endurance of England and the preservation of the Christian church itself.

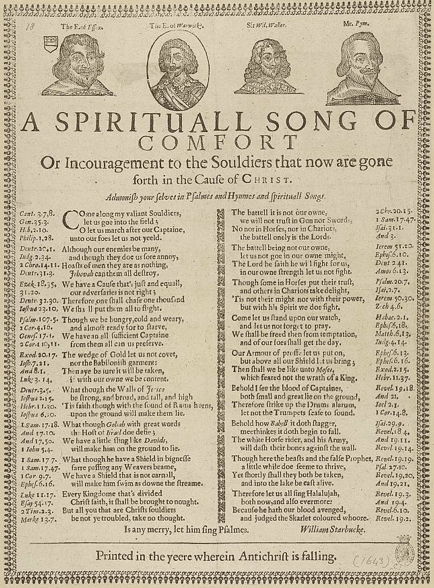

One Warrior Man ballad of note, fittingly titled “A Spirituall Song of Comfort” (http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/33240/xml), displays an especially strong propagandic lean in favor of the parliamentarian contingent of the English Civil War. Written by William Starbucke at an unknown date (though the year 1643 is handwritten at the bottom of the EBBA’s facsimile), the ballad addresses soldiers “that now are gone forth in the Cause of Christ,” advising them to “Admonish yourselves in Psalmes and Hynmes and spirituall Songs.” Divulging its radical Protestantism, the ballad concludes with an inscription that the ballad was “Printed in the yeere wherein Antichrist is falling.” While “Antichrist” could refer to Pope Urban VIII, who died in 1644, the statement more likely serves as a denouncement of Charles I and a “prophecy” regarding the all-but-assured failure of the royalist faction and the followers of Laudianism. As opposed to the Puritans, who “castigated the Church of England as ‘but halfly reformed,’ as a mongrel that bore too many traits of its Antichristian parent” (Walsham 921), the supporters of Archbishop William Laud “repudiated the traditional Calvinist view that the pope was Antichrist and offered a more positive analysis of the Catholic middle ages” (933). In encouraging Warrior Men to “be like unto Moses, / which feared not the wrath of a King” (55-6), the ballad participates fully in the Puritan side of English Civil War discourse by motivating its listeners to fight against Charles I, a cause apparently favored by God.

The most striking features of “A Spirituall Song of Comfort” are the four woodcuts which accompany the ballad, each of which depict a leading member of the Parliamentarian cause. Unlike the woodcuts featured throughout the greater corpus of early modern British ballads, which are often reused and may correspond only marginally with the content of a given text, the English Broadside Ballad Archive has no further record of the use of this ballad’s unique and crucially thematic woodcuts. The figure of Robert Devereux, the third earl of Essex and commander of “the Parliamentary army against Charles I’s force in the first three years of the English Civil Wars” (“Robert Devereux, 3rd earl of Essex”), appears in the upper left-hand corner of the page. To his right is Robert Rich, the staunchly Puritan second earl of Warwick and fleet admiral who “secured the adherence of the navy to the Parliamentary cause in the English Civil Wars” (“Robert Rich, 2nd earl of Warwick”). Sir William Waller comes next, a “leading Parliamentary commander in southern England during the first three years of the Civil War” and a “leader of the Presbyterians in Parliament” (“Sir William Waller”). The last figure is of John Pym, a “prominent member of the English Parliament (1621-43) and an architect of Parliament’s victory over King Charles I in the first phase of the English Civil War” (“John Pym”). In actively fighting against the perceived oppression of the monarchy and simultaneously rejecting the “papist” leanings of Laudianism, these well-known parliamentarians embody a propagandic image of the “ideal” Protestant Christian who fights in favor of religious reform. In presenting images of ideal spiritual warriors, the woodcuts implore the ballad’s audience of Warrior Men to follow such examples by fighting for the “God-ordained” rebel cause.

The other extraordinary features of Starbucke’s ballad include the Biblical marginalia and allusions scattered throughout the text, each of which may have aimed to inspire Warrior Men while justifying the rebellion against Charles I. Notably, Starbucke pairs each of the seventy-two lines of his ballad with glosses which reference scripture from both the Old and New Testaments. The themes of the ballad and of the corresponding scriptural passages intersect suitably in nearly every instance: for example, “Although our enemies be many” (5) has been fittingly matched with Deuteronomy 20:1: “When thou shalt go forth to war against thine enemies, and shalt see… people more than thou, be not afraid of them.” In this way, the ballad joins a widespread Protestant tradition of scouring the Bible for verses which uphold reformist doctrines, a practice which concurrently provides the Warrior Man with rhetorical and scriptural persuasion to join the fight. As such, the ballad directs its audience toward the book of Revelation:

Though here the beasts and false Prophet,

(65-72)

A little while doe seeme to thrive,

Yet shortly they shall be both be taken,

And into the lake be cast alive.

…

Therefore let us all sing Halalujah,

Both now, and also evermore:

Because he hath our blood avenged,

And judged the Skarlet coloured whoore.

Starbucke’s marginalia associate his discussion of the Whore of Babylon and the false prophet found in Revelation 19:2 and 19:19 with the Church of Rome and the Pope, respectively. This advances a propagandic interpretation of scripture which justifies the rejection and expulsion of Catholic influence in England, as well as the Catholic church’s defeat on a larger scale. Beyond offering messages of spiritual comfort to its audience, the ballad calls on Warrior Men to join in the parliamentarian movement, offering themselves in service to a cause which corresponds with the Biblical defeat of evil.

Though authored several decades after “A Spirituall Song of Comfort,” Warrior Men Ballads which relate the events of the Williamite-Jacobite War argue for a similar advancement of Protestant aims in England. This is apparent in “A new Song, As it is Sung upon the Walls of London-Derry” (http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/22270/image), a ballad reportedly orated by “an Honest Protestant Commander” of the Williamite faction. The siege of Londonderry follows the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when “James II, a Catholic, was deposed by his Protestant daughter, Mary, and her husband, William of Orange, in a bloodless coup” (“Siege of Derry begins”). After seeking exile in France and soliciting the aid of the French army, James “landed in Ireland, hoping to incite his Catholic supporters there and regain the British throne” (“Siege of Derry begins”). Viewing the Jacobite force from the ramparts of the city, our Protestant Commander and narrator of the ballad shouts his bold refrain: “We’d fight all, bleed all, dye all, / e’re Bloody Papists should get the day” (23-4). Diction labelling the Jacobite forces as “Papists” continues throughout the remainder of the ballad:

Though Papists Rejoyce, and fain wou’d see

(25-8, 49-52)

The Fall of Englands Liberty,

Yet we that have God and the King of our side,

The cause of all this will decide:

…

In England they have done the same,

The Papists there are come to shame;

And here with us they look’d like Lambs,

With their Cheats and Popish Shamms.

In addition to the thrice-repeated references to the Papacy, which coincide with the apparent loss of England’s “liberty,” this excerpt asserts that “God” has joined sides with the King, William of Orange. The ballad then celebrates the removal of James II, an action which brought the Papists “to shame” in England, while desiring a similar victory in Ireland. Yet the ballad’s audience would likely have already known the results of the battle; indeed, the Protestant belligerents successfully defied James II’s army for 105 days before the arrival of British reinforcements. For Warrior Men, the ballad offers evidence that God favors the Protestant Williamite faction in allowing their victory against Catholic forces, a struggle which has not yet reached its conclusion by the time of the ballad’s publication in 1689. Thus, the ballad’s call to “Fight all, bleed al, dye all, / till we free England from all their Harms” (55-6) is truly a propagandic message aiming to incite the patriotism and religiosity of Warrior Men, that they might join the fight in advancement of the Protestant understanding of the “true” religion. Here, I will also briefly note an intersection in themes between the Warrior Men and Dugaw Warrior Women ballads. “The Protestant Commander” (http://estc.bl.uk/R182219), though still framed by the romance of the Warrior Woman and her lover, begins with the male soldier’s endorsement of William of Orange: “Farewell, my sweet lady, my love, and delight, / Under great king William in person I’ll fight” (1-2). Though perhaps not indicative of the wider corpus of Warrior Women ballads and the themes found therein, “The Protestant Commander” lends further credence to the notion that 17th-Century street literature often functioned as political and religious propaganda.

The final ballad I will examine in this essay, “The Siege of London-Derry, or the Church Militant” (http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/22272/xml), also endorses the aims of William of Orange and the Protestant soldiers defending Ireland from James’ army. The ballad’s title lines give particular attention to “Collonel Walker’s Speech, whereby he preswaded his Besieged Soldiers, to continue Stead-fast, Valiant, and Couragious, a little before they Obtained the last Great Victory over the Enemy.” The ballad’s commemoration of George Walker, “the joint governor of the town and an Anglican clergyman [who] gave inspired public sermons that roused the people to a fierce resistance” (“Siege of Derry begins”), echoes Starbucke’s celebration of the four Protestant parliamentarians featured in “A Spirituall Song of Comfort.” Like Essex, Warwick, Waller, and Pym, Walker becomes a paragon of the Warrior Man, someone who fights against James’ oppressiveness and is willing to die as a “martyr” for the Protestant cause. Reportedly offering a “sum” of Walker’s own diction, the ballad then denounces the “Popish King, / Who would us under Slavery bring” (14-5) while claiming boldly, “Our King is Faith’s Defender” (8). In its fifth stanza, the ballad plainly reveals the identity of this kingly “Defender of the Faith”:

William’s One against them all:

(35-9)

He knows both Sea and Land too.

The Orange was our Antidote,

‘Gainst Mother Church, and Popish Plot:

That threaten’d English both and Scot.

The ballad unabashedly endorses the Glorious Revolution and the military campaigns of William of Orange as the “cures” for England’s political and religious strife (though it notably fails to mention Mary II, William’s wife and the joint monarch of England). Yet William of Orange cannot be successful on his own; as such, the ballad concludes with a pointed message encouraging Warrior Men to join the newly installed Protestant King: “Then be at His Command now… Both Faith and Charity they want. / Then Live or Dye, be never Faint; / Nor have a thought of flying” (40, 46-8). Propagandic to its core, “The Siege of London-Derry” argues that Warrior Men who join the Williamite faction will also become defenders of the “true religion,” a cause which must prevail if England is to overcome the perceived ideological dogma of Catholicism.

Though the themes and generic frameworks of 17th-century street literature are diverse, ballads which feature Warrior Men and overarching themes of wars and battles serve distinct political and religious propagandic purposes. As they argue in favor of continued religious reform in England while subsequently rejecting Catholic political figureheads, these ballads attempt to convince soldiers to offer themselves in service to the Protestant cause. In this way, the Warrior Man ballad diverges in content and purpose from the generally romantic (although sometimes also subtly propagandic) Warrior Women ballads. Though it may contain romantic themes in its various iterations, the Warrior Man ballad pays particularly close attention to the way war thrusts common men into a spiritual quandary between an individual’s nationalistic pride and their perception of their own mortality. In response, the Warrior Man ballad craftily reassures its audience of soldiers by invoking the name God (and presupposing God’s will). In asserting that God has ordained his favor upon the English Protestant Reformation and forces which seeks its advancement, the Warrior Man ballad becomes a message of propaganda invoking the support of the early modern commoner.

fig. 1: Facsimile of William Starbucke’s “A SPIRITUALL SONG OF COMFORT”

Works Cited

Fumerton, Patricia. “The Ballad’s Seaman: A Constant Parting.” Unsettled: The Culture of Mobility and the Working Poor in Early Modern England. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006. 131-152.

Pound, Louise. “The English Ballads and the Church.” PMLA, vol. 35, no. 2, 1920, 161-188.

Wilsham, Alexandra. “History, Memory, and the English Reformation.” The Historical Journal, vol. 55, no. 4, December 2012, 899-938.

Würzbach, Natascha. The Rise of the English Street Ballad, 1550-1650. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

EBBA22270, Pepys Library, Pepys Ballads 5.50. http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/22270/xml

EBBA22272, Pepys Library, Pepys Ballads 5.52. http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/22272/xml

EBBA33240, National Library of Scotland, Crawford.EB.228. http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ballad/33240/xml

“John Pym.” Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 26 June 2019.

“Robert Devereux, 3rd earl of Essex.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 10 September 2019.

“Robert Rich, 2nd earl of Warwick.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 21 June 2019.

“Siege of Derry begins.” History, A&E Television Networks, 9 February 2010.

“Sir William Waller.” Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 15 September 2019.

“The Protestant Commander.” The Dugaw Catalogue, 362-4.