Sarah Chapman

Diane Dugaw’s collection of ballads contain several that take place in the Americas; including North America and the Caribbean. However, in her work as a scholar, Dugaw does not highlight differences between ballads taking place in England and those from America. Her primary focus as a folklorist is narrative structure, which does not vary from country to country, according to popular folklore scholarship from Vladimir Propp. If we look at these specific ballads through the lens of those taking place in America, an interesting pattern starts to emerge. America is a fulfilment of fantasies-whether those fantasies are to get rid of a new lover, or to start a new life. However, for many characters in these ballads, the Americas hold more horrors than joys.

In this essay, I will be examining several ballads that take place in the Americas, including “The Female Sailor Bold”, “The Dublin Tragedy”, “New York Streets”, and “The Loyal Lovers Garland”. All of these ballads take place after the initial colonization of the Americas. “The Loyal Lovers Garland” is dated in the English Short Title Catalog as written between 1745 and 1755, right around the time of the French and Indian War and increases in slave trade through Jamaica and Barbados. “New York Streets” was written between 1815 and 1820. “The Dublin Tragedy” has a rough time frame of between 1787-1791. The only ballad we have a definitive date on is “The Female Sailor Bold”, which references 1825 in its paratext as the year Ann Jane Thornton was revealed as a woman after returning to London. I will be using these rough time frames to establish contexts for each of these ballads: what was happening in America to inspire British balladeers to write about them? The difference between ballads taking place in England versus the ones taking place in America is evident through the context of wars and trade conflicts established within the ballads. There is also clear evidence of racial conflicts of the day involving slavery and indentured servitude. These ideas were brought to America from the British colonization and importing of people and exporting of products facilitated by the slave trade.

The Loyal Lovers Garland

Chronologically, “The Loyal Lovers Garland” is the first to take place, according to Dugaw’s citations at the beginning of the ballad. In this ballad, a merchant’s daughter falls in love with a sailor. She is rich and he is poor; therefore, her father disapproves of their love. The sailor is sent to Barbados (it is unclear the reason why) and he continues to send letters to his love back in England. Her father intercepts one of these letters and sends the sailor into exile on the island while the ship continues on with its mission. The merchant’s daughter, after finding out what her father has done, resolves to dress as a man and get a ride on a ship to try and find her love. The ship is sailing towards Jamaica, but by some lucky chance, they happen upon the island where the sailor has been abandoned. Reunited, the lovers immediately sail back to England to convince the father of their love and to be married. Ignoring the compelling love story momentarily and looking at the movement of ships in the ballad, we can see another story.

The ballad begins with: “a ship for her father was just come from sea, with some young ladies on board she did go, the ship and the rich cargo to view” (580). Clearly, the merchant and his daughter are well off, as he frowns upon her marrying someone poor like a soldier when “Many rich squires of honor and fame a courting unto this lady came”. At this time, products like raw sugar (including cane sugar and beet sugar) were some of the only imports coming into Britain from Jamaica and other Caribbean islands. British refiners, those who turned sugar from a plant into consumable product, charged huge tariffs on exporting sugar, eventually pushing other colonizing nations like France out of the trade (Gordon 3). British investors and merchants, much like the one in “The Loyal Lovers Garland”, were able to get rich on these tariffs and create their own nouveau-riche class. In addition to using natives or imported slaves to farm the land, Britain also sent over employees as overseers and farm workers. “Nearly all prosperous colonists returned to England by the 1730’s. In so far as they were concerned any increase in employment because of their demands for goods and services would be only in production for home consumption” (Gordon 5).

In the ballad, the sailor sends a letter to his love from Barbados, which her father intercepts. “When did you hear from Jemmy your dear; he’s now at Barbadoes, and fit to come home” (581). Many Englishmen were sent to Barbados as indentured servants, earning their freedom after five years of work on a plantation with slaves, who were never able to be freed. Because of the increasing income disparity between white, British landlords and the population working the fields, several slave rebellions happened in the early 18th century, right about the time when this ballad may have been written (Zinn 42). It is plausible that the sailor was sent to Barbados under the arrangement of an indentured servitude cultivated by the merchant. This would have gotten him out of his daughter’s reach for at least 5 years until Jemmy could earn enough money to buy a return trip to England. There are references to the sailor as “a beggar” and “poor”, which suggests that not only is his occupation as a sailor not making him much money, but that he can’t even afford to take his own journey to Barbados without becoming an indentured servant. Since sailing had recently gone from a profession (skilled labor) to wage labor (unskilled), the social stigma surrounding sailors was more prominent than in decades previous.

In “The Loyal Lovers Garland” in particular, Barbados, Jamaica, and the other islands of the West Indies are used as a site for banishment. This is where the rich from England send their unsavory or unsightly folks and brought back the luxury goods they had come to appreciate, like sugar and tobacco. They are sent far away to an island where it is likely they could die of starvation or mistreatment (as the sailor almost does). If they do manage to buy a passage back to England, they will be unrecognizable because of their time spent in this subordinate position (Zinn 45). For the British in these ballads, America is a land “out of sight, out of mind” capable of getting rid of any problems you might have. However, for those who are sent there against their will, like soldiers and the enslaved, America can turn out to be a harsh landscape full of unfamiliar enemies.

The Dublin Tragedy

In “The Dublin Tragedy”, a merchant’s daughter- with a fortune of two thousand pounds- fell in love with an Ensign in the army. They decide to get married with the merchant’s daughter’s warning: “When that my father he does come to know,/ if you disloyal be, or inconstant to me,/ my tender heart will break with grief and woe.” The Ensign replies with “If I prove false or inconstant to thee,/ may cruel fortune on me still attend;/ and may I never thrive, or prosper while alive,/ but make my exit by a shameful end” (754). He gets called for duty “over to old England as we understand” and she decides to dress as a man and follow him on the ship as a passenger. She brings lots of jewels and money with her to Stratford where the couple got married. Then they sailed to America with the regiment; her as an ensign and him as a lieutenant “with what gold they brought, they both commissions bought”. They head to America where they are captured as prisoners. When they were released from prison, the lieutenant stole all of her money and sailed off to Dublin where he got married and kept a shop. She eventually finds out his secret after being forced to become a beggar on the streets of London. “Some halfpence she had got with which she poison bought” and then “vowing revenge unto him for the deed” she makes him watch her grim death (755).

In this ballad, America is painted as a hostile place that makes people do crazy things. “In nine long weeks or more they reached that bloody shore, where hostile danger raged on every side, nothing but smoke and fire seen thro’ wood and mire” (754). They are forced to walk through “frost and snow” and sleep in “open fields with nothing for her covering by the sky”. Using clues left in the ballad, we can surmise that this ballad takes place sometime shortly after the Revolutionary War. She goes to Fort Montgomery in New York where she “acted gallantly”, to Saratoga where she “bore command” and finally was taken with Burgeyn. Fort Montgomery was a strategic location used by Native Americans travelling between New York and Canada in the 1700’s and was seized for use in the War of 1812 by US military forces. Saratoga, also in New York, was the site of a hugely influential battle in the Revolutionary War in 1777. This battle gave the Americans an advantage over the British, led by General Burgoyne. This is most likely the battle she fought in, as evidenced by the similarity of locations and the name of the General. “Likewise at Saratoga bore command, and there at length we find was taken with Burgeyn, tho’ like a valiant soldier she did stand” (755). During the historic battle, Burgoyne found himself trapped by American forces, so he retreated to Saratoga and surrendered his entire army there. It is possible that the Warrior woman in “The Dublin Tragedy” was one of the members of the army taken prisoner with her husband and Burgoyne. Since Lake Chaplain was used as a route for British forces to get supplies during this battle, I think it is highly likely that the “Fort Montgomery” reference earlier is referring to this trade route from Canada to New York. Using these clues, this would put the ballad taking place around 1777, when the battle of Saratoga took place. Since we know the outcome of the lovers in the ballad: the man leaves the warrior woman and steals all her money to open a shop in Dublin, gets remarried, and eventually is killed by the warrior woman, it makes sense that it was written after the War had finished. The “Fort Montgomery” mentioned in the ballad is the name given to the site at Lake Chaplain in the early 19th century, which could be when the ballad was composed. It is possible that placing the ballad in a recognizable battle during the Revolutionary war could lend historical accuracy to the existence of this particular warrior woman. Or, it could be a cautionary tale to men about marrying a woman who wants so badly to go into the army with you. Unlike some of the other ballads in the collection, this one does not end in a happy ending with the lovers getting married after a big reveal. This one ends with a theft and subsequent suicide of the warrior woman because of what the soldier did to her. The positioning of this ballad around a specific historical event could give validity and plausibility to the tale for future soldiers heading to America.

New York Streets

“New York Streets” is a ballad about a Squire’s daughter who falls for the Footman. The Squire finds out and he sends the Footman away to sea. The daughter then dresses as a man and follows him to America. While there, she walks through a forest, meets some unfriendly natives, and kills one of them. She flees to a sea-port town where she catches a ship to Jamaica. In Jamaica, she is found by an English ship captain and becomes a worker on his ship in exchange for passage back to England. The ship wrecks and they are stuck on a lifeboat with nothing to eat. Starving, they decide to kill one of their own and eat them. As fate would have it, the Footman is the one who will have to kill the Warrior Woman disguised on this boat. They realize who the other one is, but before they actually have to kill the woman for survival, the captain spots a ship in the distance. These ships rescue the crew and they all sail to London. The Captain finds the Squire, explains the situation, and, overjoyed with the news, the couple gets married with the Squire’s blessing.

Much like “Loyal Lovers Garland”, the characters end up in an indentured servitude position in Jamaica. However, the woman in this ballad is using her servitude to gain passage back to England. In the first ballad, Jamaica/Barbados is a destination for punishment, whereas in “New York Streets”, it is a destination for salvation against the cruel mainland. The squire’s daughter first ends up at Fort St. George. This was a site of a Revolutionary War battle in New York in 1780. If we take this as the location (influenced by the title of the ballad), the attack on her by Indians, referenced as “Rogues”, reinforces the stereotypes against Native Americans as savage and brutal. “And travelling through a forest there, two Indian men she chanc’d to meet, who like two Rogues resolved were, in a vile Manner her to greet” (626). However, she draws out her Rapier and kills one of the men in the struggle while the other one runs away in fear. Since she attacked the “Rogues” back, the power is put back into the white hands, as is typically the case with British/Indian conflicts. Unfortunately, the Fort St. George in Long Island was burned down shortly after the battle and present day nothing remains of the site. There is another Fort St. George in India as well. This was a British outpost founded in 1644 by the East India Company as a trading post from which a town came to life. The reference to “Indians” in the ballad could theoretically be talking about people from India, although based on the title “New York Streets” I think this is unlikely.

This ballad has a few different variations in Dugaw’s catalog as well. In the second one, subtitled “Silk Merchant’s Daughter”, she sails to a “distant land” where her lover has gone “to serve the King” (631). Instead of heading to Jamaica and finding her lover there, she finds a ship bound for Germany where she runs into her lover on the street. The ballad uses language similar to that used in slave passages from Africa to America when their boat is wrecked. “Thirty-seven hands were confin’d in a boat, I which a small allowance of room they did float; when food was all gone, death appeared so nigh, The Captain made lots for to see who first must die” (632). De-personalization of passengers was a common trope when referring to slaves. The passengers are also referred to as “figures”. Because of this language, and the fact that the ship sails to Germany instead of Jamaica, it is plausible that this ballad could have taken place at the Fort St. George in India rather than in New York. The significance of using depersonalized language in reference to sailing on a boat too small for that many people is the clear difference in circumstances between the situation of slaves and the Warrior Woman’s crew. Slaves were forced onto a ship with not enough room and made to sleep so close together that disease was rampant. According to Slavevoyages.org, a database of all slave voyages from 1500-1800, approximately 80% of slaves traded between Great Britain and the Americas made it to their destination. However, the conditions on many ships left slaves sickly or dead.

“On one occasion, hearing a great noise from below decks where the blacks were chained together, the sailors opened the hatches and found the slaves in different stages of suffocation, many dead, some having killed others in desperate attempts to breathe. Slaves often jumped overboard to drown rather than continue their suffering. To one observer a slave-deck was ‘so covered with blood and mucus that it resembled a slaughterhouse’” (Zinn 29).

Their choices were limited to jumping overboard, dying of suffocation, or risking the unknown horrors of the New World. On the other hand, the Warrior Woman’s ship is put into the situation through a set of unfortunate circumstances, and when they run out of food, they have the agency to decide whether to eat one of their crew or suffer starvation. While it may have seemed desperate to the crew of the ship, chances were that most of them would make it out alive. The slaves on ships did not have such a choice; whether they were pushed to the point of starvation or not. The power dynamics between these two groups are immensely different. For the most part, the people on the Captain’s boat know they will make it out alive and with a familiar station in life. For slaves being transported to the New World, there was no guarantee they would make it there alive, or that their life would be anything like what they were used to dealing with in their home countries.

The question then remains: is this variant actually called “New York Streets” or did Dugaw title it that in order to group in in with these other ballads specifically referencing New York and Jamaica? References to the second variation of this ballad online are only found through Dugaw’s book and her catalogue, so we have to go based off of her citations. There is evidence of her separating ballads with extremely similar themes and characters, such as “The Female Sailor Bold”, “The Female Sailor”, and “The Female Sailor Ann Jane Thornton”. Thinking of it this way, I assume that the second ballad variation was called “New York Streets” and one would not know the difference in meanings or context without doing research on the two different Fort St. Georges. British ballad hawkers could have also heard the first variation and changed locations mentioned in the ballads to sell the same story to different audiences. The meaning between the two versions changes the way it is read. If it is based in America, there is racialized language towards Native Americans and allusions to the slave trade. If based somewhere else, the ethical implications of using this type of language are greatly diminished.

The Female Sailor Bold

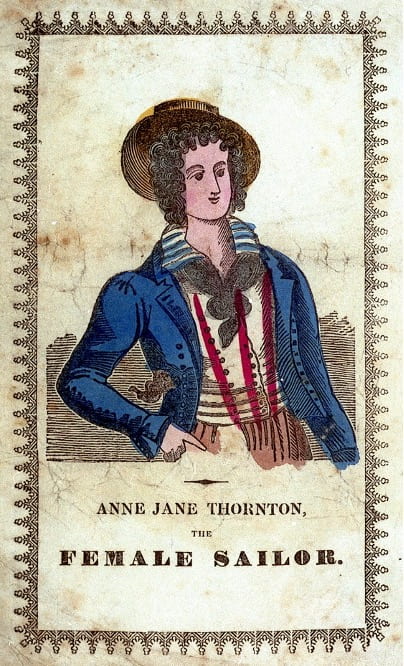

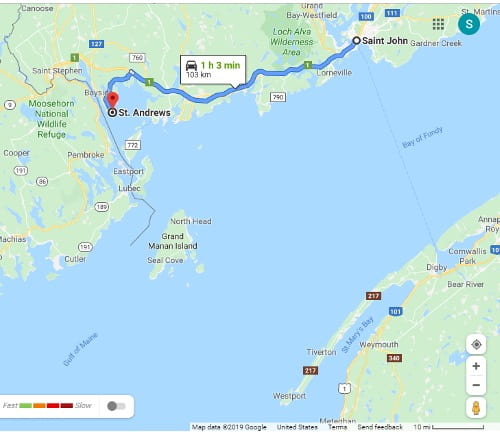

In the ballad “The Female Sailor Bold”, we get the story of Anne Jane Thornton, a woman who dressed as a boy and sailed out to sea. She was famous in her time, approximately 1820-1840, and warranted people writing ballads about her; several different versions of it as recorded in Dugaw’s catalogue. Unlike any of the other ballads, this one is accompanied by a short biography of Anne Jane Thornton before the ballad so the reader knows this story is based in fact. She sailed across the ocean to America to follow a Captain whom she loved. She first landed in New York and after being told her lover had died, she travelled around America serving on several ships disguised as a boy. She served on the Adelaide and the Rover as a steward, then travelled home to London from St. Andrew’s in Maine on the Sarah. When she got to London, the Lord Mayor had her investigated, “that the lordship might hear the remarkable details of the case from the girl’s own lips” (788). While she had “performed the duties of a sailor admirably”, she had a hard time running up the sail during severe weather. Her hands “appeared as if they were covered with thick brown leather gloves”, uncommon on a woman. According to her testimony, “America was no place in which to look for sympathy” (789). The myth of “pulling yourself up by the bootstraps” and of the American spirit seems to have been well ingrained by this time in the 19th century. She travelled 70 miles by foot from East Point to St. Andrews because she didn’t want to take sympathy from anyone. Unlike “New York Streets”, Anne was not attacked by Indians, nor does she describe being treated any way but respectably while she was on her adventures. Perhaps she appeared more tough and manly than the other women depicted in these ballads. Or the vison of America depicted in these later ballads has changed from the early days; America is now a place for new identity formation, not so much a place of danger and rebellion.

In the next ballad in Dugaw’s catalog, “The Female Sailor”, the story is fairly similar. She falls in love with a sailor named William Brown. When he leaves for Liverpool, she resolves to follow him, but when she got there, she found out that he had already been sent to St. Johns in America. When she gets there, she is told that he has died, so she cut off her “golden locks” and put on her “blue jacket and trowsers” (796). She was hired as a cook and steward on a ship where she lived for three years (much like Anne Thornton). The captain discovers she is a woman and then decides to marry her. The slight differences in these two ballads illustrate the mutability of stories like “The Female Sailor Bold”. The original story was worn out, so someone decided to re-word some of the sections and sell it as a brand-new ballad. Like the difference in “New York Streets”, I think these two ballads offer similar enough content to infer that they are variations on the same story. The second one however, does not mention any names, therefore a reader could apply any character to the warrior woman in the ballad, not necessarily a historical figure. Anne Thornton heads off from St. Andrew’s in (what is now) Maine, whereas the Female Sailor sails from St. Johns in New Brunswick, Canada. The two cities are very close to each other, only about 100km or 64 miles. Belfast is referenced in these ballads and instead of being the one in Ireland, it could be the city in Maine; a short boat ride away from either of those coastal towns.

America, and Canada, seems to be the place where the Female Sailor found solace. It wasn’t horrifying, or a place to send an unwanted visitor. This could be the difference in the depictions of Northern states/countries, like upstate New York or Canada, and depictions of southern locations like Long Island, Jamaica, or Barbados. In the British imagination, the northern part is most similar to their own country. They colonized it, then when eventually the colonies rebelled, they accepted them as a new nation. On the other hand, Jamaica and Barbados represent money and power to the British empire. Britain sends indentured servants and slaves there to plant and harvest crops like sugar, then charges then a huge tariff on the finished product. Northern America is seen as an equal, a land of opportunity that you shouldn’t mess with, whereas the Caribbean islands are a source of exploitable income. In other words, for the British, the Americas represent a complication of attitudes about the New World. Depending on who you were talking to, it could simultaneously be a land of opportunity and mutable identities, like Anne Jane Thornton, or it could be the home of rebels and slaves to make you money. All of these ballads represent different sides of America to the British Empire in different periods of history.

In looking at collections outside of Dugaw’s work, I am sure a similar pattern would emerge with references to different parts of the Americas representing conflicting attitudes within the empire. Within Dugaw’s catalogue, the selection of ballads set in America, reinforce the ideas of Warrior Women as against the norm and people who would rather see adventure with their lovers instead of staying home and missing all the action.

Works Cited

“Anne Jane Thornton, the Female Sailor”. National Maritme Museum. Greenwich, London. Image.

Gordon, William E. “Imperial Policy Decisions In The Economic History Of Jamaica, 1664-1934.” Social and Economic Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 1957, pp. 1–28. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27851084.

Millard, James P. “Following Fort ‘Blunder’… The Strange and Sad Tale of Fort Montgomery” http://www.historiclakes.org/explore/Montgomery.html

“The Battle of Saratoga”. US History.org. US History Online Textbook. http://www.ushistory.org/us/11g.asp

Hanc, John. “Discovering the Forgotten British Forts of Revolutionary Long Island”. January 24, 2019. https://www.newsday.com/long-island/discovering-long-islands-revolutionary-era-british-forts-1.26281907

Zinn, Howard. “Persons of Mean and Vile Condition” in A People’s History of the United States. Pg. 39-58.

“Slave Voyages”. Emory Libraries and Information Technology. https://www.slavevoyages.org/

From Dugaw’s Catalogue

“The Dublin Tragedy, or the Unfortunate Merchant’s Daughter”. Dugaw Sequence Number 84. Page 752-756.

“The Female Sailor Bold”. Dugaw Sequence Number 91. Page 785-792.

“The Female Sailor”. Dugaw Sequence Number 92. Page 793-800.

“The Loyal Lovers Garland”. Dugaw Sequence Number 52. Page 578-584.

“New York Streets”. Dugaw Sequence Number 59. Page 623-636.