By Mackenzie Devine, Denise Schell, and Kelly Plante

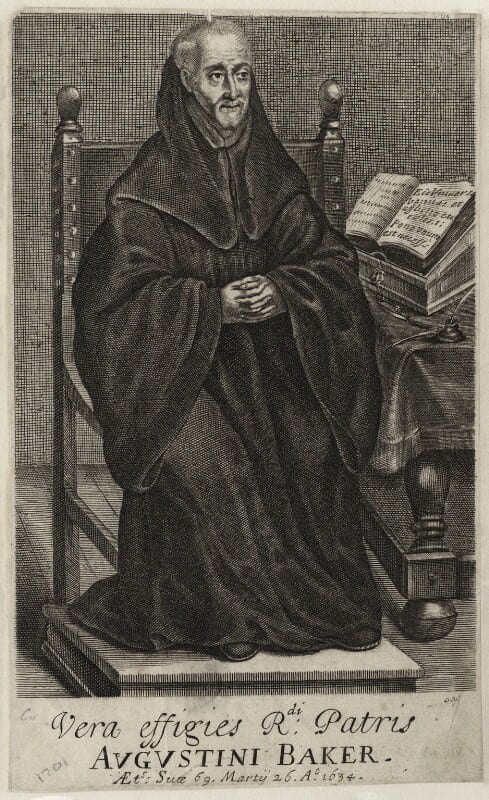

Augustine Baker (given name, Augustine; professed 1605, d. 1641), spiritual advisor to Gertrude More, was born on December 9, 1575 in Abergavenny, Monmouthshire in South East Wales as the thirteenth and last child of William and Maud Baker. Abergavenny had a high concentration of Catholics at that time, even though dissenting from Protestantism could lead to persecution or death (Temple 22). Baker’s family had originally been Catholic, like many of their neighbors, but converted to the Church of England before he was born. As a young adult, he described his religion as neutral (Temple 22). In 1596, he studied law at the Inns of Court in London but, due to the death of his older brother, Richard, never finished his degree.

While fulfilling Richard’s responsibilities as Recorder of Abergavenny, Baker nearly died crossing a bridge on horseback in a torrential storm. He viewed his survival as a miracle—his “Road to Damascus” moment of conversion—and he began to immerse himself in Catholic works such as classic mystic texts by St John of the Cross and St Teresa of Avila, which he would later encourage the Cambrai nuns to read. As Liam Temple puts it, he essentially “read himself” into Catholicism (Temple 23). For Baker, Catholic mystics “outlined a ‘higher strain of spirituality’” that convinced him of the sanctity of the Catholic faith and confirmed his “calling to a life of monasticism” (Temple 23). Baker took the name Augustine, probably in honor of the great theologian St Augustine of Hippo, when he became a novice in the Benedictine order on May 27, 1605, in the monastery of St Justina at Padua.

Meanwhile, the “revival of the English Benedictine Congregation and a revival of mysticism in monastic circles” were both underway (Temple 20). Baker used his legal training as a means of “effecting the continuance of the . . . pre-reformation English Benedictine Congregation, [which] survived . . . in the person of one monk only, Fr. Sigebert Buckley of the Abbey of Westminster” (Hogg xxi). This process united Englishmen who had professed within various congregations of the Benedictine order under the same congregation to which Buckley belonged, allowing the English Benedictine Congregation to survive and be recognized as legitimate within the Catholic Church. At the request of his superiors, Baker began to gather spiritual and religious materials for Clement Reyner’s 1626 book, Apostolatus Benedictinorum in Anglia [The Apostleship of the Benedictines in England], which further supported the restoration of the English Benedictine Congregation.

In 1624, Baker arrived at the newly founded English convent in Cambrai, where he served as an unofficial spiritual guide to the house. In the course of his reading and research, Baker had come upon several works of medieval mysticism which struck a deep chord in him, and he drew liberally upon these works in order to create a distinctive contemplative program for the convent. His sources included Latin, German, Spanish, English and Italian texts that spanned several centuries, with some dating back as far as the 8th century. Father Baker composed many spiritual treatises for the nuns at Cambrai, and he also translated mystic works into English for the convent. Interestingly, he provided the Cambrai house with access to the writings of both male and female religious figures. In the process, Baker created a library for the convent (Rhodes), which included texts such as “The Quiet of the soule” (159), based on Juan de Bonilla’s A short treatise of the quiet of the soul; “St Tiresia her life” (160-161); and “the Clowde” (166), based on the mystical tome The Cloud of Unknowing.

Baker’s mysticism was “centered around the reading and adaption of previous works of mystical experience to build a ‘canon’ of what he referred to as ‘mystick authors’” (Temple 25). As a result, the Benedictine nuns who would become his followers were “highly productive both textually and spiritually, identifying that reading and writing could satisfy their evolving personal and communal needs” (Temple 25). Baker also believed “each soul was to be ‘left to itselfe & to the guidance of the divine spirit.’ Individual experience, as well as ‘divine grace and lighte’ would ‘teach him both the matter & manner of her prayer’” (Temple 26). However, Baker’s opponents objected strenuously to the way that his methods encouraged autonomy among the nuns (Temple 30). Since “Baker considered God to be the one true ‘prime guide’ to the mystical life” (Temple 30), the confessor’s role as an intermediary between the nuns and God in convents such as Cambrai was greatly lessened. According to Baker’s mysticism, nuns were to “‘follow [their] owne observation & experience’” (Temple 31).

This method appealed to Gertrude More, whose spiritual journey was, like Baker’s, filled with dramatic twists. More’s father was the primary patron of the Cambrai convent, and in 1620, she was compelled to join as one of the original members after her mother’s death. Unlike her sisters, More did not initially feel a calling to the vocation of a nun. Her “lively and spirited” personality was not well-suited to monastic life (Datta 57), which ideally entailed subordination of self-will and seamless incorporation of the individual into the collective identity of the cloister. When Baker arrived at the monastery in Cambrai, More was one of his most outspoken and contentious detractors, sending frequent missives to the English Benedictine Congregation in order to register her concerns and complaints. Gradually, though, she opened up to him regarding her doubts about her fitness as a nun and sought his counsel. After finding that his instructions were helping her find peace in monastic life, More became one of his most ardent supporters.

Because Baker’s teachings emphasized personal connection to God through mental prayer, More at last felt free to “live the contemplative life in a way that suited her temperament” (Datta 57). More’s mysticism “was characterized by difficult periods of divine or ‘interior darkness’ which she often described as ‘loving God without Confort [sic]’” (Temple 32). Baker’s mystic influence deeply informs her works, many of which revolve around “divine darkness, individual spiritual guidance from God and complete obedience to the divine will” (Temple 32). More’s writing illuminates her desire for mystical experience “beyond all words, one in which God was experienced through union and taught the soul directly” (Temple 33), thus bearing witness that she was one of Baker’s most fervent, vocal, and star protégés.

Yet while many nuns found solace in Baker’s “way of love,” others decried his approach as unorthodox and thus problematic. Father Francis Hull, the official chaplain at Cambrai, was disturbed by Baker’s assertion that confessors were unnecessary because it undermined Hull’s authority within the convent. Hull filed a complaint against Baker to the General Chapter of the English Benedictine Congregation, alleging that Baker’s teachings were anti-authoritarian and heretical. Thanks in part to More, who argued that Hull had been suspicious of Baker since his arrival and that most of Hull’s accusations were a product of paranoia (Temple 40), the General Chapter vindicated Baker and allowed the convent to keep his writings. Despite this outcome, both men were removed to restore harmony at Cambrai.

After Baker penned an ill-advised and scathing portrait of the prior at his new monastery, the president of the English Benedictine Congregation intervened to remove him from that house as well. At an advanced age, Baker was sent to the English mission, which he happened to vocally oppose. He died three years later of a fever. Even after his death in 1641, Baker’s mysticism continued to attract scandal. However, his instinct to use his star pupil’s writing to secure his own legacy turned out to be a sound one. More’s writings, steeped in Baker’s mysticism, preserved his legacy as a mystic authority with trans-denominational appeal. Even in death, More continues to advocate for Baker and his mysticism, through her writing.

Works Cited

Bellenger, Aidan. “Augustine Baker in his Recusant and Benedictine Context.” That Mysterious Man: Essays on Augustine Baker with Eighteen Illustrations, ed. Michael Woodward, Analecta Cartusiana, pp. 42-56. Three Peaks Press, 2001.

Datta, Kitty. “Women, Authority, and Mysticism: The Case of Dame Gertrude More (1606-33).” Literature and Gender: Essays for Jasodhara Bagchi, eds. Supriya Chaudhuri and Sajni Mukherji, pp. 50-68. Orient Longman, 2002.

Rhodes, J.T. “Dom Augustine Baker’s Reading Lists.” The Downside Review, vol. 111, 1993, pp. 157-73.

Salvin, Peter and Serenus Cressy. The Life of Father Augustine Baker, O.S.B.: (1575-1641), eds. Dom Justin McCann and James Hogg. Universität Salzburg, Institut für Anglistik Und Amerikanistik, 1997.

Temple, Liam. Mysticism in Early Modern England, pp. 19-44. The Boydell Press, 2019.