By Vicky Beacham, Brenda Kizy, and Kelly Plante

In the early to mid 1600s, the lives of Augustine Baker and Gertrude More intersected at the English Benedictine cloister at Cambrai, where Baker served as an unofficial spiritual advisor to the nuns, including More, until the power struggle between Baker and the convent’s confessor, Francis Hull, led to their mutual removal.

Baker had entered the Benedictine order as a novice in 1603 and professed as a Benedictine monk in 1607 (Rees 2). During his residence at Cambrai he took the Englishwomen under his wing for their spiritual formation (Rees 3). Baker did not support the dominant spiritual exercises in Benedictine convents at that time, such as rote prayer (repetition of memorized prayers, such as the rosary) or the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises (a program of guided meditations). Furthermore, he did not think that contemplation could be learned from confessors. Rather, he recommended mystical books for the nuns to read in order to discover what passages resonated with them. Baker taught that prayers should not be prescribed by a confessor but should emanate from the inherent connection between the individual and God. For Baker, contemplation was a “living tradition” that responded to the individual’s particular needs: the “distinctive notes of his doctrine were interior freedom and responsiveness to promptings of the spirit. He discouraged dependence on spiritual directors and stood loosely to external observances” (Rees 3). Baker also believed in extending prayer time for the nuns and allowing them to develop more individualized connections with God without confessors as the middlemen, ultimately giving nuns more autonomy in their spiritual lives.

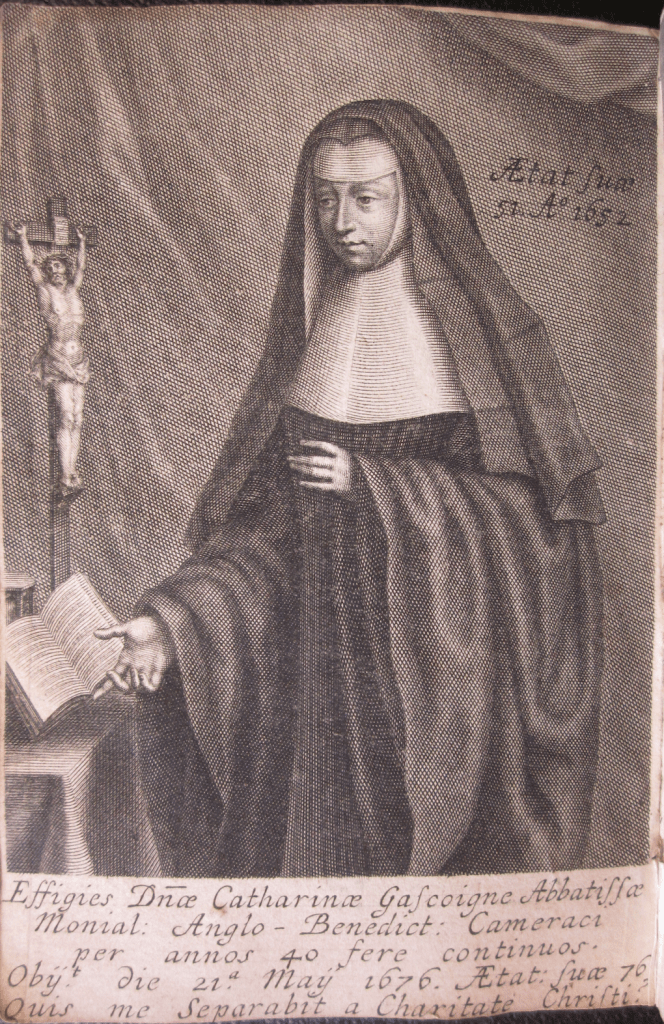

While the majority of nuns took to Baker’s ways before the arrival of Hull in 1629, the convent did not initially coalesce around Baker. Many harbored reservations about his teachings, including More. For about a year, More “decided to kill Father Baker’s influence with the deadly weapon of ridicule and set to work with a will. She derided the simplicity of his discourses and mocked those who were diligent to his instruction” (Benedictines on Stanbrook 11). Eventually, however, Baker’s philosophy of finding one’s own way appealed to More and led her to follow his methods so that she and Catherine Gascoigne (name in religion, Catherine; professed 1625, d. 1676), who had supported Baker from the start, became his staunchest supporters in the convent. By the time that the convent chose Gascoigne as its second abbess, most of the nuns had clearly chosen to follow Gascoigne and More in supporting Baker’s methods.

Baker’s teachings afforded the nuns more agency and freedom in their religion, and the notable institutional backlash against Baker attests to the radical nature of this proposition. Hull was critical of Baker’s non-traditional ways, especially since they challenged his very position at the convent. Hull was “concerned that Baker’s influence limited his own rightful authority as the house’s appointed confessor, … [and he] encouraged the nuns to follow an Ignatian method of prayer distinct from Baker’s contemplative instructions” (Goodrich 172). No written evidence exists to suggest that the nuns opposed Baker, so it is possible that his only critics at Cambrai were Hull and a few nuns. However, this could be due to the measures that the convent took to preserve Baker’s teachings: criticism was eliminated to keep his doctrines alive.

After Hull accused Baker of heresy and anti-authoritarianism, the English Benedictine Congregation conducted a thorough examination into Baker and his teachings. More expressed support for Baker’s mystical teachings through her polemical poetry as well as a prose Apology. Her verse in particular expressed her personal views on her relationship with God and prayer: views that were inspired by Baker. In her poem, “Amor Ordinem Nescit,” More makes several references to Baker’s personalized style of prayer and how she incorporates it in her relationship with God. On her love for God, she writes, “O cheer up, heart, be comforted, / For he is in thy mind; / To him relation one may have, / As often as he goes / Into the closet of his heart, / His griefs for to disclose” (ll. 51-55). These lines imply that God resides in the heart and mind of everyone and is accessible through personal prayer without a confessor—ideas which support Baker’s doctrine of interior freedom and contemplation through prayer. Further in the poem, the ideas of freedom and prayer come up again: “And I do wish with all my soul / That to thee I could pray / With all my heart and all my strength / Ten thousand times a day. / Let people, tribes, and tongues confess / Unto thy majesty” (ll. 193-98). More’s desire for more time for prayer could be a reference to the personal freedoms afforded her by Baker’s teachings: he gave them more access to praying and thus, more time. Additionally, her call for “people, tribes, and tongues” to confess to God could capitalize on the idea of people confessing and praying to God on their own without a confessor present, rendering prayer a personal act. More’s poetry was an outlet for her to express her faith as well as her support for Baker; ultimately, it became a historical resource for the controversies surrounding Baker and the convent.

More did not live to see the results of the trial; she died from smallpox before Baker was acquitted, in part thanks to her staunch defense of his methods. Although Baker left to join St Gregory’s in Douai and was not to return to Cambrai, his teachings remained important at Cambrai and ultimately influenced the English Benedictine spiritual patrimony as well as the Cambridge Platonists, the Quakers, the nonjurors, Germain pietists, and the Scottish mystics, as well (Rees 4). More’s writing also lives on today as a testimony to Baker’s teachings and the controversies of the convent.

Works Cited

Benedictines of Stanbrook. “Cambrai: Dame Catherine Gascoigne, 1600-1676.” In a Great Tradition: Tribute to Dame Laurentia McLachlan, Abbess of Stanbrook, pp. 3-29. Harper & Brothers, 1956.

Goodrich, Jaime. Faithful Translators: Authorship, Gender, and Religion in Early Modern England. Northwestern University Press, 2014.

Rees, David Daniel. “Baker, David [name in religion Augustine] (1575-1641), Benedictine monk and mystical writer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2014.