By Kay Cirocco, Julia Hodgson, and Amy Salter

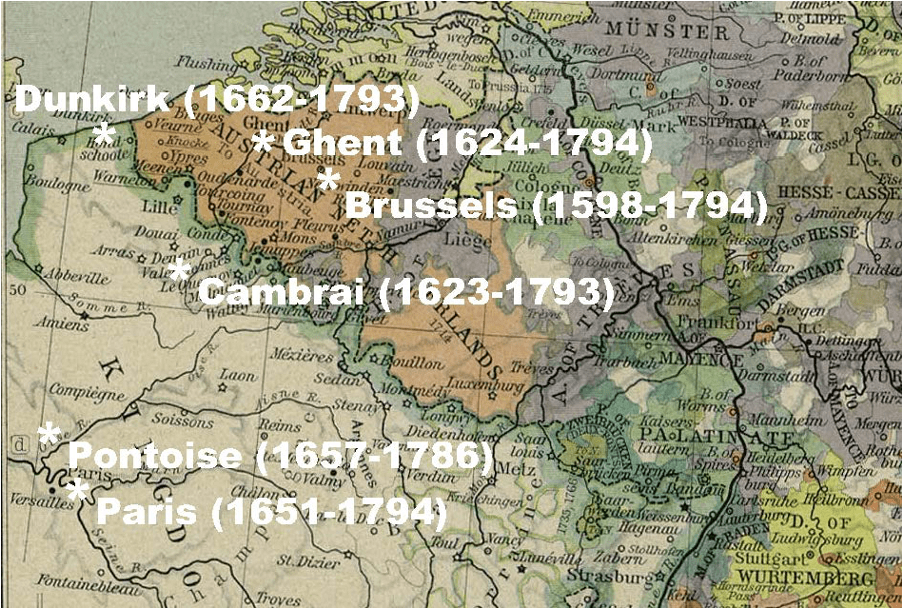

As anti-Catholic legislation became more extreme in England during the reign of Elizabeth I, demand grew for English convents in mainland Europe, where English women could take their vows without fear of persecution. The establishment of an English Benedictine convent at Brussels in 1597-98 marked the first of many such convents created to serve the English Catholic exiles of the seventeenth century, as Caroline Bowden explains in “The English Convents In Exile and Questions of National Identity.” In less than a century, twenty-two English convents were founded across Europe by a variety of orders, including the Poor Clares, Franciscans, Augustinian, Carmelites, and the aforementioned Benedictines, which Gertrude More joined. Once founded each convent established their own unique culture, structure of governance, and rules for religious life specific to their sect, location, and ethnic identity (Bowden, “English Convents in Exile” 298).

While no two convents were identical in operation, they each required two things to survive: the ability to attract English women with sufficient dowries to maintain the house’s existence and a formal relationship with male clergy within the Catholic Church. These clergy members served as spiritual directors and confessors who were sent to the convents in order to guide nuns in monastic piety as well as day-to-day functions of the convent (Bowden, “Introduction”).Nevertheless, clashes involving confessors could also prove dangerous for these institutions. Gertrude More, an English Benedictine nun at Cambrai, became involved in a well-documented feud between spiritual advisor Augustine Baker and confessor Francis Hull, who came to the convent in 1624 and 1632 respectively. This initial turmoil, however, proved to be ultimately inconsequential to the convent’s stability; Cambrai weathered the death of More and the relocation of Baker and Hull in 1633.

Between 1600 and 1800, there were many other kinds of disruptions in recruitment besides disputes over confessors. Bowden writes, “it has been argued that the English Civil War had a major impact on convent recruitment as it is interrupted the movement of candidates and the money needed to pay their dowries” (“Introduction” xxi). In addition, English Catholics back at home paid close attention to the overall reputation of each convent, which influenced their decisions about where to send their daughters. Bowden writes that a major issue for English convents was that “parents needed reassurance that they were committing their daughters to well-managed institutions with a reputation for religious observance and discipline” (Bowden, “Introduction” xiv). Family networks were of the utmost importance when it came to recruiting would-be nuns. Some common surnames found at the convents included Percy, Sheldon, Petre, Bedingfield, Howard, Plowden, and Arundell. Thus, many women in these convents were sisters, aunts, and nieces to one another. Despite constant difficulties in recruitment, by 1800 around 4,000 women had entered the English convents, with only 143 coming from the relatively small Benedictine house at Cambrai.

One of the major reasons that English Catholics supported these monasteries was that the English convents sought to harbor and preserve English Catholicism with the hope of one day returning the religion to England. After joining the convents, English nuns made the most of their isolation by negotiating the terms of their existence and achieving spiritual and political stature in the wider community (Walker 177). The convents offered generations of Catholic women an opportunity to pursue their religion without persecution, while displaying their nonconformity to the Protestant church and state in an even more overt rejection of English religion, law, and society (Walker 2). Because the nuns were kept apart from their families as well as the English Catholic population, the convents operated as dislocated pockets of resistance to mainstream Protestantism in England. As a result, the identities of the nuns were bound closely by their proximity to the English martyrs (such as More’s great-great grandfather, Thomas More) who sacrificed their lives for the preservation of their faith.

The convents on the Continent in the early modern period provided vital spaces for English Catholic women to practice religious resistance, as well as to pursue closeness in a community that encourages political and spiritual standing. These women were so devoted to their faith that they willingly gave up their relationships with their families and their homeland to spend their lives abroad in the convents. Continental convents provided English women the opportunity to practice Catholicism safely, surrounded by others with similar beliefs until the turn of the eighteenth century, when they would migrate back to England.

- 625 monasteries and convents suppressed by Henry VIII, 1536-1541

- 22 English convents established on Continent, 1598-1665

- 4,000 women joined these convents, 1598-1800

- 1,000+ manuscripts produced by these convents, 1598-1800

Works Cited

Bowden, Caroline. “Introduction.” English Convents in Exile: 1600-1800, vol. 1, pp. xi-xlv. Pickering & Chatto, 2012.

—. “The English Convents in Exile and Questions of National Identity 1600-1688.” British and Irish Emigrants and Exiles in Europe, 1603-1688, ed. David Worthington, pp. 297-314. Brill, 2010.

Walker, Claire. Gender and Politics in Early Modern Europe: English Convents in France and the Low Countries. Palgrave MacMillan, 2003.